Everything old is new again

Updated: 2013-07-03 05:46

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Limelight | Mao Weitao

Mao Weitao could have rested on laurels, but she is willing to take risks to keep her art form relevant and resonating with audiences. She not only loves Yue Opera but also wants to expand its appeal, writes Raymond Zhou.

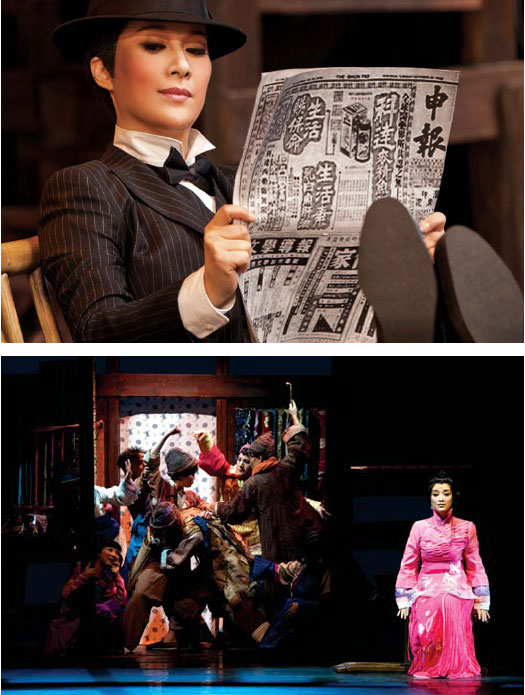

German playwright Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) never set foot in China, and he mistook Sichuan province for a city when he wrote The Good Person of Szechwan. Now his classic play about the difficulty of doing good while everyone gets busy doing well is reincarnated as a Chinese opera - but set in another part of China. Not only does the story fit the locale perfectly, but also it has become a star vehicle for an artist who has specialized in transgender roles throughout her career - similar to trouser roles in Italian opera. When Mao Weitao makes an entrance as the female Shen Teh, there is a frisson of excitement in the audience. It is the first time Mao, superstar of Yue Opera, has ever played a role in her own gender. And what a gorgeous and feminine portrayal!

Of course, Mao gets to impersonate the alter ego of Shen Teh, her invented cousin Shui Ta, the ruthless young man. The onstage gender reversals go beyond a plot device and reach a rare transcendence where the performer-character duality is blurred into a surreal totality. A female star who plays only male parts now takes on a female role who often passes as a man. It is somewhat like Viola in Shakespeare in Love who disguises herself as a man to play a woman in a no-girls-allowed stage culture.

"I never work myself into the illusion that I'm male so that I can be believable onstage," Mao says. "I'm always a woman playing men. The audience won't be fooled into thinking I'm a man."

As a matter of fact, the audience does not even need to go near the stage to know that. Zhejiang Xiaobaihua Yue Opera Troupe, of which Mao Weitao is president as well as the biggest star, has an all-female cast. And the art form as a whole is predominantly female-oriented, with only a few male performers who were incorporated in the 1980s as an experiment. But it's funny that when Yue Opera first evolved in 1906, the actors were all male, just as in Peking Opera.

Yue is the name of the ancient kingdom that is now Zhejiang province. Yue Opera, previously translated as Shaoxing Opera - perhaps to avoid confusion with Cantonese Opera, which is also pronounced Yue Opera in Mandarin - first flourished in the 1930s when it migrated north to Shanghai.

The pioneers of this local performing art borrowed extensively from Kunqu Opera, China's oldest extant opera, and spoken plays, which are imported from the Western world. It is less stylized than Peking Opera and more natural in its expressions, hence lending itself to portrayals of love stories that are more tender than passionate. In a way, this is a reflection of the local personality.

Though all first-generation Yue Opera artists were women from rural Zhejiang, some of them displayed a keen affinity for socio-realism. The late 1940s saw a production about a country woman who suffers endless misery - contemporary with the era. The unvarnished depiction of poverty and cruelty is adapted from a Lu Xun story.

Half a century later, Mao brought another of Lu Xun's iconic stories to the stage. Kong Yiji is the ultimate loser, unsuccessful at the imperial entrance exams and failing to adapt to reality. Mao shaved her head to tackle this totally unglamorous role, at the risk of alienating her phalanx of fans. Mao is arguably the greatest innovator of her generation not only for Yue Opera but also for all traditional Chinese operas.

Giants like Mei Lanfang experimented with new repertory when Peking Opera was on the rise. Mao faces a much tougher choice: innovate or die. All Chinese opera forms are fast shrinking in audience size. Yue Opera is among the lucky few with a sizeable base, albeit elderly women for a large part.

"It's easier for me to explore new territories because our art form is only 100 years old," Mao explains. "But Peking Opera is 200 years old and Kunqu is 600 years old. They'll encounter more resistance than I would."

The seeds of innovation were planted in the 1980s when Mao failed her college entrance exam. To make up for what she perceives to be her failure at higher education, she immersed herself in the intellectual pursuits of the day, such as reading newly permitted philosophy and literature from Western countries, frequenting fine arts exhibitions and befriending modern dancers.

"People say an actor of traditional opera does not need 'depth', but I believe the opposite. Such an actor should be able to jump out of his or her own field and examine it from another perspective. Only then can one excel in his or her profession," Mao says.

While she was rising fast on the opera stage, this kind of intellectual exposure brought her a breadth of knowledge almost unparalleled in her own circle. And it certainly helped that her husband, Guo Xiaonan, is trained in theater but has a family background in traditional Chinese opera - a different form from Yue Opera though.

Mao's determination to stem the decline of audience members by broadening not just the repertoire but also the artistic idiom of the form has repeatedly made headlines. For the centennial celebration of Yue Opera in 2006, she produced The Butterfly Lovers, an opera made famous through numerous productions and a movie musical. Yet, Mao was able to breathe new life into what is often called the Chinese Romeo and Juliet, although the narrative actually resembles Yentl more closely.

A young woman in ancient China disguises herself as a man so that she can be enrolled in school. She meets a classmate and falls in love with him, but cannot bring herself to divulge her secret. In Mao's retelling, the shift of the male lead's friendship into romantic love has been made less sudden and more logical.

"If we had followed the original production, today's young audiences would read his feelings for her as homosexual sentiments as, for a long time, he did not know her true gender," Mao notes.

While retaining the best-known arias, Mao tinkered with many musical passages to find the best expression for the drama. She even borrowed the theme from the violin concerto version, which was inspired by Yue Opera in the first place, for a heart-achingly lyrical moment.

Visually, the stage did away with realistic sets and used an iron-cast structure that is abstract, yet expressive, capturing the essence of the story rather than architectural details. Traditional hand-held fans are used as a major prop. The whole production has a cleaner and classier look that seems to be inspired by a Chinese poem.

For her new production of The Good Person of Szechwan, now renamed The Good Person of Jiangnan - Jiangnan refers to the Yangtze River Delta - the musical idioms are so much richer, with hip-hop for comedic effect and a Pingtan melody as a leitmotif for the appearance of the lead in female form - Pingtan is a Suzhou-based storytelling form of singing - and a Broadway-style number for the factory scene.

Amazingly, the opera does not look like a jumble but like a fresher form of Yue Opera or even Yue Opera meets stage musical. All the explorations in artistic expressions serve to bring out the poignancy and relevancy of the story, which fits contemporary China more than any other time, even though it is set in the early 20th century.

Mao is a conscious innovator, and she constantly agonizes over the difficulty of attracting young theatergoers.

"What can I do to enhance the appeal of Yue Opera and at the same time retain its core values?" she often asks herself.

She knows she is not living in the best era for her art form and is sometimes reminded that, had she worked in another medium, she might have achieved more.

"Any form of culture has its own season to bloom," she says. "We may not be in this season, but we can be steppingstones toward the next."

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 07/03/2013 page18)

Today's Top News

'Positive' sign on Asia-Pacific free trade pact

Venezuela eyed as Snowden's asylum

FM responds to Manila's accusations

Credit crunch hits smaller firms

Chinese firms eye strong EU brands

China faces long battle in drug crackdown

Sea center looking for candidates

Xinjiang offers rewards for tips

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|