Master of an ancient Miao folk dance

Updated: 2012-02-02 07:58

By Qiu Bo (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

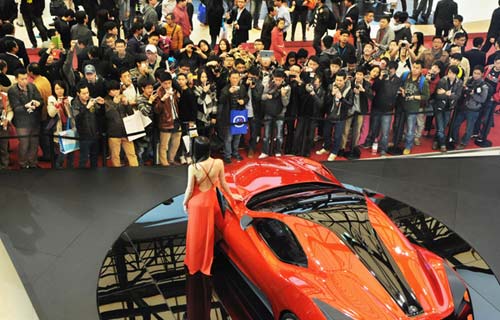

Lan Heng (left) performs changshanlong, a traditional Miao folk dance, with his fellow villagers in Sizhai, a remote Miao village in Southwest China's Guizhou province, on Jan 17. Provided to China Daily |

GUIDING, Guizhou - An ethnic dance unique to a remote Miao village has been off limits to outsiders for more than 1,000 years.

Until now.

As the inheritor of a tradition handed down for 35 generations, Lan Heng has made it his mission to teach the dance to those beyond the village's borders to keep it alive.

"Several decades ago, only two successors were allowed to learn this folk dance in the village for each generation," Lan said.

He is one of them.

In recent years, however, that rule has been broken and now about 20 villagers in Gusa, in Southwest China's Guizhou province, have mastered the dance.

"My late father taught me how to dance and he warned me not to leak this folk art out of the village," the 35-year-old said.

Changshanlong is a traditional Miao folk dance performed on the 31st day after China's Lunar New Year's day, when the whole village carries out a spring-cleaning and shuts down.

"Any guest from outside Gusa is not welcomed when we perform the dance," he said.

Residents in Gusa are from one of the Miao branches who believe their ancestor is Heimanlong, a general who pledged his loyalty to Yue Fei, a legendary Han marshal who fought the Jurchens' invasion during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

After Yue Fei died for his nation, the sad Miao general stopped eating and died of starvation.

The sacrificial ceremony, in which a cow is slaughtered, is held in honor of him.

The performers wear locally-made black costumes, put on makeup and dress up as dragons, dancing in rhythm while playing a reed pipe, a Miao traditional musical instrument.

"The dance has eight basic choreographic movements to copy the dragon's move, but since the number of performers can be from one to more than a thousand, there are hundreds of group moves," said Lan, adding it is quite a complicated dance.

Since the year 2007, some 200 junior-grade students have been learning from Lan at school.

"As a folk class, it is a required course rather than optional," he said.

"I'm the first and only teacher delivering changshanlong to students," said Lan, the pride showing on his face.

In 2006, the dance was designated a national intangible cultural heritage by the Ministry of Culture, helping Lan obtain a permanent position at the school.

However, Lan's teaching has faced countless unfriendly comments from fellow villagers.

"The old rule forbids us to teach the dance outside the village," Lan said. "Old villagers especially felt that I was breaking the rule."

But he insists he did the right thing.

"The dance is not suitable for the old men, but young people have been seeking job opportunities outside and no one wants to learn this dance."

"The dance is facing the risk of disappearing," he said. "It's my mission to let more people learn changshanlong, though I know there's a debate."

"It's an interesting class," said 15-year-old Luo Shichao. He said it took him more than a year to learn to play the reed pipe. "But I think it's worth the time as I enjoy it."

Lan maintains a special performing team with 12 outstanding students.

"My team is invited to perform outside the county each year and they don't have to rehearse before they perform."

The team even performed on China Central Television.

"Lan has dedicated himself to delivering the folk dance and we respect him," said Zhou Zhengxiang, the 37-year-old headmaster.

Zhou's school spends around 20,000 yuan ($3,180) to buy costumes and musical instruments each year for Lan's class.

"My current wish is to perform the dance in overseas countries," said Lan. "The folk art will live as long as more and more people know and enjoy it."

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|