The write stuff

Updated: 2012-01-31 08:00

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

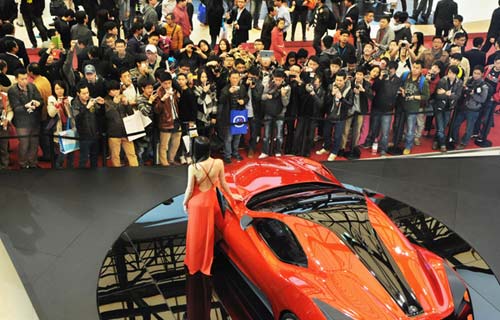

Li Tusheng spent 10 years to finish a 10-volume book of Chinese classics in handwritten calligraphy. Photos by Mei Jia / China Daily |

|

A scroll of Li Tusheng's Collection of Manuscripts of Asian Classics. |

Li Tusheng is multitalented but his calligraphy works are particularly valued, and his latest 10-volume book was 10 years in the making. Mei Jia reports.

To those who know him, Li Tusheng is a miracle man. He was taught Shaolin kungfu by his father as a child, has defeated martial arts challengers from many nations and can predict the future or determine feng shui through understanding the Book of Changes, his fans say.

He is also a talented calligrapher who sold one work - with just three characters - for 267,000 yuan ($42,300) at an auction in Beijing in 2010.

Li says he wears a lot of hats.

"But I see myself principally as a lover of traditional Chinese culture," he says. "I want to be an inheritor of our culture, because it's where national pride comes from."

For Li, traditional culture is "the root of culture".

Born in 1953 in Dongyang, Zhejiang province, he is a self-funded researcher based in Beijing. In December, he published a 10-volume book of Chinese classics in handwritten calligraphy called Li Tusheng's Collection of Manuscripts of Asian Classics.

It has 360,000 characters and is 640 meters in length. The content includes Confucian works, the Four Books and the Five Classics, Buddhist sutras, and historical and literary masterpieces.

"When words are spoken, they leave no trace," Li says. "But when words are recorded by hand, they're passed on."

He started the project 10 years ago, when he was living in a Buddhist temple. There, he copied the Buddhist scriptures for two years, in the distinctive calligraphic style developed from the so-called "big-character posters" of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

"Brush writing is like doing tai chi. The continuity of qi is important," Li says. "I was concentrating so much on writing that I forgot to eat or sleep and didn't know whether it was day or night."

Even so, errors were unavoidable, Li says, and he occasionally had to trash a script as long as 4 meters when a ringing phone disturbed him and caused him to make a mistake.

Zhao Changqing, of the Chinese Calligraphers Association, says: "In a computerized era, when people are losing the ability to write by hand, Li offers an example of respecting tradition with action."

Li Peiyu, with Beijing Daily, says the book is valuable because it provides an accessible approach to the Chinese classics, saving the trouble of checking in libraries to locate rare versions.

Li says he adopts different styles when he writes, according to the content and atmosphere of the manuscripts.

"When the content is sublime and serious, I use regular kai script, but when it is easy and unrestrained, I use the 'running', or xingshu script," he says.

Li says he turned down a 100 million yuan offer to buy all the manuscripts because he believes the work should not belong to a private collector but rather to the nation.

What really lends value to the volumes, as calligrapher Zhao points out, is that Li writes with a solid understanding of each character.

"I think knowing about the characters, their origins, their evolution through the various dynasties and their structures is fundamental to a calligrapher," he says.

Li has spent years researching more than 7,000 frequently used characters. His collected thoughts about these were published in his magnum opus in 2009, called Tusheng's Collection of Explanations of Chinese Characters, which was 8 million characters long.

He's often invited to give lectures abroad. He says that after a speech to some 400 people at Harvard University in 2003, he explained the Chinese character for country () as part of his answer to a students' question about whether China would be a "major threat".

"I told them the element, which partly means weapon (), is created within the bigger square frame () that stands for Chinese territory," he says, "So, that means Chinese people, typically, will guard their land but never launch an aggressive action outside their territory."

Li often takes notes, when he has time, about the misuse of words in the media, in the hope that language is used correctly. He also writes down his thoughts about the differences among Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, using simple phrases.

Li was in the army from 1973 to 1991, where he exercised his ability to memorize and perform mental arithmetic.

After that, he established a small company to support his research of Chinese characters.

"Though he's not an academic, he is unique in having absorbed so much knowledge," Li Peiyu says.

Li Tusheng also practices what he preaches. For instance, when it comes to filial respect, a traditional Chinese moral imperative, his is not limited to his 85-year-old mother but extends to other old people, too. Li is a frequent visitor to the senior citizens' house in his neighborhood. He tries to bring happiness to them by performing magic and providing gifts.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|