Stitches in time

Updated: 2012-01-26 09:41

By Huang Zhiling (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

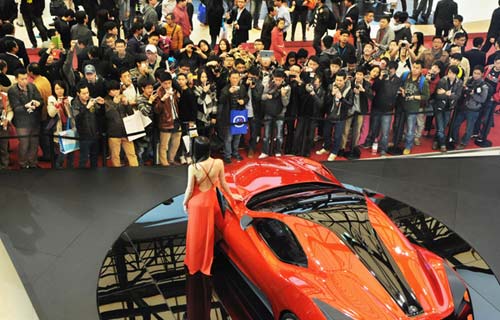

Weavers operate a dahualou loom at the Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum. The ancient loom is made entirely of wood, without a single nail. Photos by Liu Yuanqi / For China Daily |

|

|

Zhong Bingzhang is curator of the Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum. |

|

|

Exhibits present Shu brocades and embroideries at the museum. |

Exhibits at the Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum show changes in the social fabric throughout history. Huang Zhiling reports.

To visit the Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum is to view the unfolding of the social fabric of what today is Sichuan's provincial capital Chengdu over the millennia, as each display is akin to a stitch in time. And it provides a look into the future of this ancient art form that is named on the UNESCO and national intangible cultural heritage lists and had virtually vanished about a decade ago.

In addition to ancient artifacts, museum guests can also see two weavers operating a hualou loom.

That sight takes 72-year-old visitor Liu Yuhong back. "It reminds me of the good old days, when making things took longer but was more environmentally friendly," Liu says.

Hualou, which literally translates as "big jacquard platform", is a loom invented in the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). It is made entirely out of wood and doesn't use a single nail. Its parts are easily disassembled and moved.

The brocade museum's original hualou is one of only three in the country. The other two are in the National Museum of China in Beijing and the Sichuan Provincial Museum, says professor Tu Hengxian of the College of Textiles of the Shanghai-based Donghua University (formerly China Textile University).

Tu is a member of an expert panel under the Ministry of Culture that selects items for China's intangible cultural heritage list.

The Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum presents looms, representative works of Shu brocades from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) to the Qing dynasties and dragon robes worn by emperors of different ages. It also sells modern Shu brocades and embroideries.

The museum reveals the past of the South Silk Road, starting from two millennia ago, not only through its ancient artifacts but also through a fresco that portrays silk productions' 12 processes.

The museum has become a must-see for visitors to the 3,000-year-old city, because it showcases one of the most important local cultural symbols," Sichuan Provincial Tourism Administration chief Hao Kangli says.

China's sericulture began in Sichuan more than 4,000 years ago, when the province was the kingdom of Shu.

Shu is the oldest of the four most famous types of brocade and is the oldest form, from which the others developed.

Shu brocades were exported throughout Asia via the South Silk Road during the Warring States Period (403-221 BC).

The ancient trade route started in Chengdu, passed through Yunnan province and then went on to Myanmar, India, Central Asia and Europe. It started 200 years before the North Silk Road, says Tu, who has studied Shu brocades for 29 years.

Shu brocades' trade was so important that the Western Han emperors appointed an official with the title Brocade Officer. His role was supervise the highly lucrative industry that operated more than 200,000 looms in its heyday.

Tsinghua University professor Huang Nengfu likens the Brocade Officer to today's minister of textiles.

Since that time, Chengdu has been known as "Brocade City" and the city moat, in which brocades were soaked to preserve their colors, is called the "Brocade River".

Chengdu had more than 2,000 private workshops and more than 10,000 looms producing brocades in the Qing era.

Chengdu set up the State-owned Chengdu Shu Brocade Factory in 1951. It employed more than 2,000 weavers.

The factory specialized in mass-producing silk for clothing and bedcovers.

"It introduced mechanical production in the early 1960s because manual weaving cost more time and money," 84-year-old weaver Xie Huiru, who started learning brocade-making at age 9, recalls.

The factory's products sold well from the early 1950s to the early '90s. Market changes in 1995 put the factory out of business a year later.

Sichuan natives would present newlyweds brocaded bedcovers featuring images of dragons (representing men) and phoenixes (representing women). But the tradition faded with the growing popularity of duvets.

Zhong Bingzhang, chief of the general office of the State-owned Chengdu Silk Corporation, which oversaw the city's silk industry, worried the tradition might vanish entirely.

So she began visiting the bankrupt factory's technicians and workers to find a solution.

Her research culminated in a report sent to Chengdu's then mayor, Li Chuncheng, in 2002.

Zhong's proposal was to use tourism and marketable products to preserve the ancient skill. After the municipal government endorsed Zhong's report, she opened the Shu Brocade Institute at the site of the former Chengdu Shu Brocade Factory.

The brand, which literally translates as "River of Sichuan", comes from what Japanese students studying in China in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) called the brocades they took home, Tu says.

Zhong invited several elderly weavers from the out-of-business factory to manually weave in the academy. Most were older than 70, because the number of people who could still do such work "could be counted on two hands".

It's monotonous. It often takes an entire day to weave 5-6 cm.

"I once spent a week finishing a brocade piece the size of a small handkerchief," He Bin, a 47-year-old who works as weaver in the museum, says.

Xie says the only reason he started weaving was to earn rice. He had been orphaned a year before he started working the looms.

Zhong has been hunting for new students to learn from masters like Xie among underprivileged families in Sichuan's economically distressed city of Xichang, where silk production remains a pillar industry. She believes Xichang residents are exceptionally hardworking, she says.

The more marketable new brocades can be used for interior decorations, fashion designs and luxury goods, Zhong says.

The academy has enjoyed a growing number of visitors, and its annual sales now surpass 20 million yuan ($3.14 million).

Zhong also established four Shujiang Brocade shops along the city's busy business streets and near tourism sites.

But the 30 million-yuan museum remains the centerpiece of Shu brocades' preservation - the main thread that holds this tradition together in modern times.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|