Books

Right to rewrite?

Updated: 2011-08-19 07:58

By Chitralekha Basu (China Daily)

|

Criticism of Chinese authors includes the claim the only reason some have an international following is because their translators have done such a great job. Chitralekha Basu stirs up a hornet's nest.

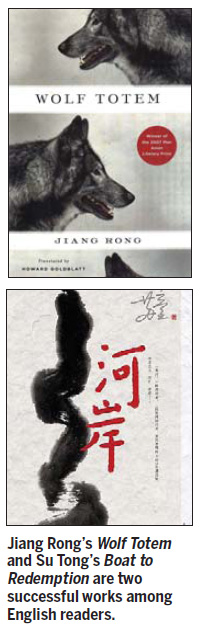

At a recent public event in Beijing, Bonn University academic Wolfgang Kubin reiterated how disappointed he was with Chinese fiction in its current state. A passionate advocate of contemporary Chinese poetry and an acclaimed translator, Kubin says Chinese novelists cannot handle long works of fiction. Kubin attributes the success of Jiang Rong (Wolf Totem), Su Tong (The Boat to Redemption) and Bi Feiyu (Three Sisters) in the international arena to the intervention of translators who, he says, are rewriting the original texts to make them more presentable to a Western audience.

Significantly, the translator of all three books mentioned above is Howard Goldblatt, a professor of Chinese at the University of Notre Dame, and generally recognized as the doyen among the translators of Chinese fiction in English, with more than 40 titles in print.

Kubin's take on Goldblatt's staggering pile of translations is this: "Goldblatt summarizes in his own English what the Chinese novelist in question might have wanted to say. He irons out the flaws in the original text. Sometimes he drops paragraphs altogether and deletes culture-specific references to make the text more accessible to Western readers. The end product is significantly different from the original."

One can't be too certain as to whether Kubin is lauding or critiquing the translator. "Goldblatt created a Chinese author for the world market and turned an unreadable Chinese work into 'world literature'," is all he would say when I prod him.

Goldblatt sounds equally ambivalent when asked to respond to the contentious issue of the translator's right to rewrite - a question that seems to turn up like a bad penny in his mailbox every other week since he published his translation of Wolf Totem in 2007.

Journalists, bloggers and dissertation-writers keep asking him why he chose to drop a large section, about 30,000 Chinese characters, from the book's postscript and glossed the reference to sky burial - thereby adding a sentence not in the original.

"I'm happy to take Wolfgang's comments as a compliment," Goldblatt says in a cryptic e-mail note. "Jiang Rong, the author, would likely disagree. But he (Kubin) gives me too much credit, since the Penguin editor's role was significant and authoritative, in that the cuts originated with her."

Editorial intervention is something that happens backstage of the translation show, unbeknownst to the reader.

Nicky Harman, who has translated several Chinese authors, including Han Dong and Hong Ying, says, "Many publishing houses have editors who will edit your translation whether you like it or not."

"If you come across a translation which has dropped a significant component of the original, don't immediately shoot down the translator. It may have been the editor who did it."

Scissor wielding is a job best left to the editors, feels Bruce Humes, who hosts Ethnic China Lit, a blog focusing on non-Han Chinese writing. As an old Chinese-to-English translation hand, who has been in the business since the 1980s and translated the hugely successful Shanghai Baby by Wei Hui, Humes sees translation as team work.

"Ideally, translators translate, proofreaders proofread and editors edit. Commissioning a translator to edit, including deleting and even rewriting, means that the translator is no longer solely dedicated to retelling the story faithfully, but is being actively encouraged to question the value of the text. For me, that would be an unwanted diversion."

Humes prefers to "stick strictly to the original" while translating a novel, providing footnotes for the editor "to explain the literal meaning of an expression that is unique to a given culture" and leave the rest to the latter's discretion.

Harman, too, prefers to translate without excision. "I'd be very loath to drop paragraphs," she says. "I can think of valid reasons why one might, but emphatically not to avoid cultural sensitivities. The danger in deleting culture-specific references is that you flatten the text and lose flavor."

Having said that, Harman agrees the Western reader may not be able to get the nuances of an alien culture. She refers to an episode in Gold Mountain Blues by Zhang Ling, a book she is translating for Penguin Canada. In it the younger of two Chinese immigrant brothers gets killed in World War II, in France. At a gala performance in honor of returning veterans the elder brother talks to the box containing the deceased's uniform. "If we come back the same way, we won't get lost ," he says.

Harman chose not to add a footnote to explain the idea that Chinese souls have to find their way home to be able to ensure a peaceful afterlife.

"I was content that the pride the elder brother feels in his dead sibling's heroism should be understood by the Western reader, and left it at that," she says.

A translator's job is often riddled with tough choices. While seasoned translator Eric Abrahamsen would like Western readers to learn to appreciate Chinese particularities, sometimes these appear somewhat idiosyncratic or plain bizarre in English. For instance, a pretty girl described as having a "goose-egg face" sounds nice in Chinese, "but not necessarily attractive or alluring in English".

While Abrahamsen is mulling over whether to "go with moon-shaped or heart-shaped, as equivalent ways of creating a similar effect in English", he admits that "part of me would really like to leave it as goose-egg".

In a way, Abrahamsen - who runs Paper Republic, a website dedicated to promoting Chinese literature among an English-speaking audience - is in agreement with Kubin's contention that Chinese fiction needs a bit of nip and tuck, to be made presentable to the world market.

"The craft of writing is not very developed or highly regarded in China, and much of what is published contains malapropisms or plain old errors that shouldn't be allowed into the translation," he says. He can see the point of editors "willing to alter the story to fit the narrative expectations of Western readers - most notably in toning down egregious melodrama, or when a writer starts sermonizing in the middle of a story."

Personally, he would rather the reader make an effort to understand the different modes of telling a story. As a translator - he has just won a National Endowment for Arts grant to translate Xu Zechen's Running Through Zhongguancun - he prefers few editorial changes and to "follow the writer" as far as possible.

"I wouldn't delete content that I thought English-language readers would find confusing because of a different cultural background - I think it's their responsibility to learn, and I think publishers underestimate readers' tolerance for details they don't understand, so long as the story is engaging," he adds.

E-paper

Going with the flow

White-collar workers find a traditional exercise helps them with the frustrations of city life

The light touch

Long way to go

Outdoor success

Specials

Star journalist remembered

Friends, colleagues attended a memorial service to pay tribute to veteran reporter Li Xing in US.

Robots seen as employer-friendly

Robots are not new to industrial manufacturing. They have been in use since the 1960s.

A prosperous future

Wedding website hopes to lure chinese couples