People

Prose and consternation

Updated: 2011-06-10 07:56

By Yang Guang (China Daily)

|

Guo Lusheng, better known as Shi Zhi, is regarded as a pioneer of contemporary Chinese poetry. Provided to China Daily |

A celebrated poet believes his troubled heart has given rise to his exceptional talents. Yang Guang reports.

The idea that distress can lead to creativity is supported by the poetic genius of Guo Lusheng. The 63-year-old, who is better known by the pen name Shi Zhi, has produced poems spread by word-of-mouth and secret handwritten notes since age 20. His three-decade struggle with mental illness began at age 25, and he was institutionalized sporadically from then until 2002. Guo's poetry anthology Winter Sun: Poem will be published by the University of Oklahoma Press this fall as the first title of the 10-volume Chinese Literature Today book series. As his translator Jonathan Stalling puts it: "The 20th century has given the world many Chinese writers with incredible stories to tell, yet few can match the nearly mythological dimensions of Guo."

Literary critic Zhang Qinghua says Guo is "without a doubt a contemporary pioneer of Chinese poetry, a singer who has guided an era since the 1960s".

Guo's style has been inherited by poets of the Misty school, a genre that emerged in reaction to the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). Bei Dao, a central figure of the school, told a French journalist in the 1980s that he began to write poems after he read Guo.

Guo has kept an extremely low profile over the years. He declined interview requests at a very rare public appearance at a seminar in late April, where he delivered a speech on his understanding of Chinese poetry.

"It's enough to read my poems and essays," he said.

Guo started writing in 1965. His early poems give voice to the aspirations of depressed young people during the "cultural revolution" and were popular among the "sent-down youth" - young urbanites like Guo ordered to toil in the countryside.

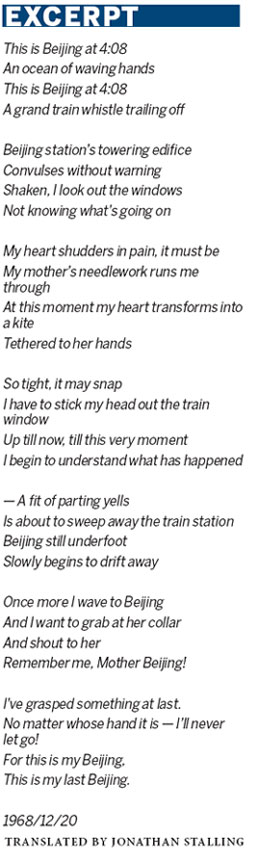

Guo recalls boarding a 4:08 pm train leaving Beijing for a small village in Shanxi province in 1968. On the train, he composed This Is Beijing at 4:08, which later became one of his representative works.

His poems provided sent-down youth reprieve from low spirits and homesickness.

Decades later, Ge Xiaoli, a Beijing youth sent to the same village as Guo, recalls watching Guo recite poems to crowds gathered in the kitchen at night.

"It was pitch dark outside," Ge writes in a commemorative essay.

"Eyes shining, Guo read Believe in the Future in the flickering light of the oil lamp with his right hand raised and pointing forward."

Guo joined the army in 1970. He fell into a deep depression after his Party membership application was shelved because he had been labeled a member of the "petty bourgeoisie" for reading foreign literature before the "cultural revolution".

"He is a sensitive and pure poet, and is susceptible to external events," his wife, 57-year-old Zhai Hanle, tells China Daily on the phone.

After he was released from military service, Guo returned to Beijing in 1973. Half a year later, he was hospitalized because of schizophrenia induced by sleeping problems, and moved out 10 months later.

He took his pen name Shi Zhi in 1978, after his mother's surname. It means "index finger", a reference to the many accusatory fingers that have been pointed at him.

In 1990, he moved into Beijing No 3 Welfare House, a mental institution in the capital's suburbs, because his mother had passed away and his father was too old to take care of him. The isolation and harshness of institutionalized life forced him to ponder existence, generating some of his most moving poems.

"Because of my dismal fate, I had little choice but to take up the pen to write about the grief in my heart, so I could achieve some sense of inner equilibrium," he wrote in his letter to US readers when the first collection of his poetry translated in English was published in World Literature Today magazine in 2007.

"It was poetry and a heart cultivated by poetry that saved my life," he says.

Zhang, the critic, says Guo's apartment in northern Beijing affords him newfound peace. He walks through, and meditates in, a small forest near his home every day.

His poetry testifies to the spiritual trials and tribulations he has faced over the decades. He wrote Believe in the Future in his 20s; To Love Life in his 30s; A Heartbroken Memory in his 40s; and To Leap over the Gorge of Spiritual Death in his 50s.

Zhang believes Guo has "never truly been clinically insane in the same way as a person who suffers from a genuine pathology".

Instead, Zhang says Guo's poetic discourse "displays a sober, sharp, profound and insightful thought process, much like the witty speech spoken by Hamlet in his melancholy".

E-paper

Harbin-ger of change

Old industrial center looks to innovation to move up the value chain

Preview of the coming issue

Chemical attraction

The reel Mao

Specials

Vice-President visits Italy

The visit is expected to lend new impetus to Sino-Italian relations.

Birthday a new 'starting point'

China's national English language newspaper aims for a top-notch international all-media group.

Sky is the limit

Chinese tycoon conjures up green dreams in Europe with solar panels