The long fight for justice

Updated: 2016-07-07 07:52

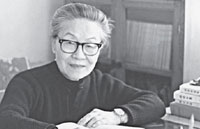

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

One woman has spent decades battling to win compensation for victims of Unit 731, the Japanese army's notorious germ warfare division. Zhao Xu reports.

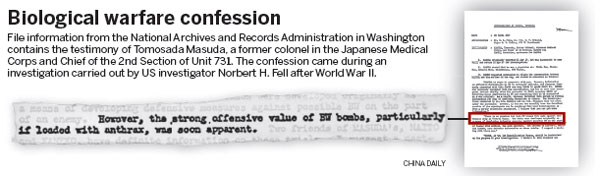

"The Japanese really did it!" Wang Xuan said, recalling her initial reaction when she discovered a crucial piece of evidence in a file at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington in 2003.

Wang is one of China's leading researchers into Japan's use of biological weapons during World War II. The file she came across contained the testimony of Tomosada Masuda, a former colonel in the Japanese Medical Corps and head of the 2nd Section of Unit 731, the Japanese Imperial Army's notorious biological and chemical warfare research and development unit.

Masuda's postwar confession came during an investigation conducted by Norbert. H. Fell, a high-profile US investigator, with Japanese diplomat Kanichiro Kamei acting as the interpreter.

"There is no question that BW (biological weapons) trials were made against the Chinese army in Central China. The bombs were originally developed as a means of developing defensive measures against possible BW on the part of an enemy," Masuda said during the interview.

"However, the strong offensive value of BW bombs, particularly if loaded with anthrax, was soon apparent."

Anthrax

The moment Wang saw the word "anthrax" her eyes opened wide. Up to that point, the 64-year-old Shanghai resident, who speaks English and Japanese, had spent two decades looking into the possible use of the bacteria by Japanese troops during WWII.

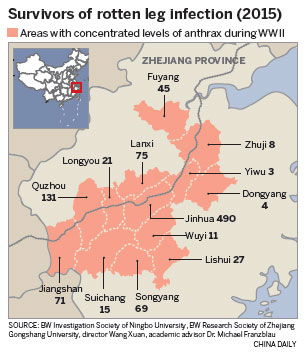

"I had talked to many elderly men and women with rotten legs in the provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi," she said. "The information we gathered, from the symptoms of the disease at its various stages to the time and scale of its outbreak, all pointed to an unnatural cause, most probably Japanese BW warfare. But still, we needed to prove it.

"The Central China mentioned in Masuda's testimony refers exactly to the areas of Zhejiang and Jiangxi, where the Japanese launched a campaign between May and August 1942," she added. "And don't be misled by the word 'trials'. Almost all Japan's use of BW during the war was dubbed 'trials' because they believed that they were still experimenting and improving their BW weapons. And, in essence, the experiments were attacks carried out, extensively and indiscriminately, against Chinese soldiers and civilians."

Between 1997 and 2007, Wang led China's largest plaintiffs' group - which had 180 members, including Wang herself - in a lawsuit against the Japanese government. The members were all victims or relatives of victims of Japan's use of germ warfare. The use of anthrax, though, was not included in the list of complaints.

Her research into anthrax attacks and the protracted court proceedings made Wang - whose late father was the first president of the Shanghai Bar Association - even more aware of the importance of the evidence.

"The initial shock and pain guided my investigations into this disease from history, which was carried out in scientific ways and advised by international scientists, experts in pathogenesis, epidemiology and other fields," she said.

One of the major challenges lies in the fact that traditional medical methods have yet to find evidence of anthrax in the victims' wounds. However, that's natural, according to Martin Furmanski, a medical scientist and historian from the United States.

"These wounds have remained open and draining since 1942, there have certainly been many opportunities for other bacteria to be introduced and become part of a 'devil's brew' of mixed bacteria," he wrote in an email to China Daily.

According to Wang, in some cases continued or repeated bacterial infection over the years have caused clots in the victim's blood vessels, which made the situation worse.

"Lack of circulation can cause ulcers on its own. For a man with rotten legs, anthrax infection more than 70 years ago set off a chain effect, long after the bacteria itself had disappeared," she said. "The complexity of the situation offers explanations not only of the many previous failed efforts to treat the ailment, but also the difficulty in establishing the fact that the disease was indeed caused by anthrax bacteria spread by the Japanese."

Retaliation

However, this doesn't mean that the history will forever remain in the shadows, or that the victims have no chance of justice.

The outbreak of rotten legs in Zhejiang and Jiangxi coincided exactly with the Japanese campaign in the provinces, and the villages that suffered most were those located either along the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Railway or nearby airbases and fields.

One example is Jiangshan county in Zhejiang. On April 18, 1942, a number of US pilots crashed in the county after conducting an air raid over Japan's larger cities. They were rescued by local people.

"Right after the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign, the Jiangshan county government conducted a survey into war damages and found numerous cases of rotting legs and bodies," Wang said.

"Of all the towns in the area, Dachen suffered the most: more than 5,000 villagers were found to have rotting patches of skin, and more than 3,000 had rotting legs," she said, quoting from records held in the Jiangshan archives. "The report didn't specify whether the figure of 5,000 included those 3,000 or not. But in either case, the numbers are enough, and could only be induced by unnatural elements."

The Japanese threw two units into the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign - the 11th and 13th armies. According to Japanese records, during the second phase of the campaign, when the Japanese army started spreading germs in the area, the 13th army saw casualties from illness soar from about 500 in the first phase to more than 10,000. "Although the soldiers had been vaccinated against a number of infectious viruses, including anthrax, it is widely believed that the Japanese biological attack rebounded on their own (troops)," Wang said.

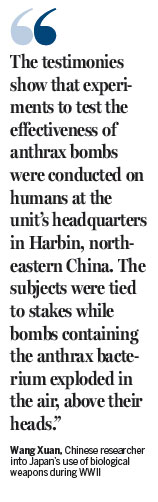

Through her research over the past two decades, Wang has met many Japanese historians of WWII, especially those focused on germ warfare. One of them was Shoji Kondo, a renowned researcher who interviewed about 300 veterans of the Japanese army after the war, including many associated with its BW programs.

"The testimonies show that experiments to test the effectiveness of anthrax bombs were conducted on humans at the unit's headquarters in Harbin in Northeast China," Wang said. "The subjects were tied to stakes while bombs containing the anthrax bacteria exploded in the air above their heads. The numerous tiny shards spread by the blasts were expected to cut through the skin to cause anthrax infection.

'Feathery material'

"On and off the battlefield, the Japanese tried many ways to spread the bacteria," said Wang, who remembers being told by an old man from Yushan county, Jiangxi province, that villagers' legs and bodies started rotting shortly after seeing "feathery material" being spread by Japanese aircraft in the summer of 1942.

"At the time, I thought he was talking nonsense. But later, when I told this to Kondo, the researcher, he said 'It could be true. Unit 731 used birds and feathers as hosts for the anthrax bacteria'."

Despite the efforts of scientists and researchers around the world, Wang said there is still much to be done before an assertion can be made in legal terms that the rotting flesh was a result of the Japanese anthrax attack.

"What I'm doing right now is building a database of similar cases during the war. And I'm also hoping the Japanese government will release more documents about Japan's wartime BW program," she said, referring to the Japanese government's persistent withholding of many wartime records.

For his part, Furmanski wondered if the illness could have been caused by glanders, an infectious disease that can result in death within days, because the Japanese army is known to have cultivated the virus and spread it in China.

"Modern 21st century methods might be applied to make a more specific scientific characterization of these outbreaks. These methods allow the detection of bacterial DNA in the pulp of the teeth of people who died of acute illnesses, where the bacteria are circulating in the blood at the time of death," he said. "If the graves of people who died during the height of the outbreak in the rotten leg villages could be located and permission to examine teeth given by relatives, it seems likely that bacterial DNA might be identified and provide a detailed look at the pathogens that killed these victims."

Between 1997 and 2007, Wang and other plaintiffs took their lawsuit from a district court in Japan to higher courts and finally the Supreme Court. Their appeals for compensation were rejected. Yet while ruling that the Chinese victims did not have the right to demand compensation from Japan, the High Court in Tokyo and the Japanese Supreme Court did uphold the verdict of the lower court that acknowledged, for the first time, that the Japanese had used biological weapons against Chinese civilians.

"Why have I gone to the courts more than 40 times? And why have I continued to search for men and women with rotting legs almost 10 years after the closure of the lawsuit?" Wang said. "It's because evil must be pursued."

(China Daily 07/07/2016 page6)

Today's Top News

Chilcot report: Iraq war based on flawed intelligence

UK invasion of Iraq was not last resort: Report

Berlusconi accepts Chinese offer for AC Milan

UK consultancy loses license, Chinese graduates being told to leave

Chinese online retailers offer 'Brexit sales' as sterling hits record lows

British PM race cut to 3 hopefuls

Suicide bombers hit three Saudi cities

Response to 'fully depend' on Manila

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|