Broadcast ban aims to keep kids out of the spotlight

Updated: 2016-05-06 08:30

By Wang Yanfei(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

China has banned children younger than 18 from appearing in reality TV shows to help them avoid potential problems caused by finding fame at an early age. Wang Yanfei reports.

Few TV programs in China earn higher, or faster, ratings than those showing how parents raise their children, especially when the parent is a chic, well-known celebrity.

Soon though, audiences will no longer be able to see this type of program because the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television recently banned children younger than 18 from appearing on TV reality shows. The move is designed to avoid the potential pitfalls of "overnight fame", according to a statement released by the administration.

The new regulations are already making an impact on what was a fast-growing industry, resulting in the immediate cancellations of some of the most popular and profitable shows that have sprung up since the 2013 launch of Dad, Where Are We Going?, the first reality show in China to feature children.

Statistics from the nation's media regulator showed that more than 100 entertainment programs were broadcast on national TV last year, and many of them were reality shows that featured children. In total, the programs generated more than 10 billion yuan ($1.5 billion) in advertising revenue.

Based on a South Korean program of the same name, the weekly Dad, Where Are We Going? featured celebrity fathers taking their offspring on camping trips and undertaking assigned tasks, such as cooking meals and building their own shelters, plus bonding by playing soccer and other sports.

The famous fathers came from diverse backgrounds, such as Jimmy Lin, a singer and actor from Taiwan, and diver Tian Liang, who won a gold medal at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney.

The first program of the final series, which was broadcast in October, attracted more than 75 million viewers, generated millions of yuan in advertising revenue and spawned a number of spinoffs, including a raft of "how to be a good parent" guidebooks.

After the show's first season, a movie of the same title nett-ed a record 700 million yuan, a feat described as a "box office miracle," by Zheng Qu, a manager with Real Dream Productions in Beijing.

Potential pitfalls

Despite overseeing the publicity campaign for the movie, Zheng now has deep concerns about the format's validity and the potentially adverse effect on the children involved: "Although it sounds a promising and easy track for people in the entertainment industry, making a profit from reality shows involving kids is not sustainable. It's also somewhat inappropriate. Reality shows such as these do more harm than good to the kids involved."

Liao Baoping, a columnist with the Yangtze River Daily, said the growing popularity of shows featuring celebrities and their children may have been the catalyst for the administration's clampdown.

"The audience is curious to see how celebrities raise kids born into rich families, and the producers have made good use of that curiosity," he said. "But the audience doesn't really learn much by watching rich, handsome celebrities and their adorable children playing games in a feel-good countryside setting."

Hunan TV has canceled the fourth season of Dad, Where Are We Going?, and has also stopped broadcasting similar shows, such as Dad is Back and My Mom is a Superwoman, on regular television, although they will be available online.

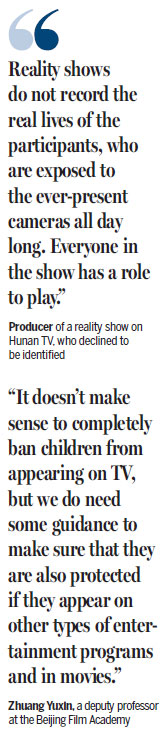

The producer of a reality show on Hunan TV, who declined to be identified, said that although the new guidelines will result in TV companies losing advertising revenue, they had to be drawn up to protect children.

"Shows involving kids initially aimed to display family love at their core, but as more and more programs emerged, the fierce competition meant we had to make more eye-catching programs to improve our ratings," he said, adding that the shows' producers exploit the fact that most viewers have little understanding of the program-making process.

"Reality shows are products. I guess the audience rarely realizes this when they watch cute kids who are prone to tantrums laughing and crying. Reality shows do not record the real lives of the participants, who are exposed to the ever-present cameras all day long. Everyone in the show has a role to play.

"It is a highly industrial production process. We used 40 cameras to shoot each episode, and the videotape of each episode was about 25 hours, which then had to be edited down to 90 minutes.

"The viewers think they are seeing the children's natural reactions to events, but after all that editing and reformatting the responses may not actually be all that genuine. What's more, some of the most-discussed scenes were engineered by a director on the set to make the story more interesting," he added.

Jiang Liang, a director of Hunan TV reality show Deformation Plan, said the artificial nature of the product is a major problem because the format makes the programs unsustainable.

"Kids in the shows look stereotypical - some look irritable, some look nice and sweet - but that's the result of cutting video clips together. How do they (the children) feel when they watch themselves on TV?

"Most people have never taken performing arts classes, and they know little about making TV programs, so it's hard to expect them to tell the difference between reality shows and reality," he said.

Liu Yan, a professor at the Institute of Early Childhood Education at Beijing Normal University, expressed similar concerns, saying hidden problems may arise when children are overexposed on TV, and that it can have a long-term impact on their lives when the show is over, especially if they have participated for several seasons spanning many months.

"Unlike shooting a film, where the kids can easily identify their given roles, children involved in reality shows may be affected later in life by everything they have experienced - the reactions of their peers on the show and the response from the public, including online bullying."

Liu used the case of Gary Chaw, a Malaysian-Chinese singer-songwriter, as an example. Chaw decided to stop updating his account on Weibo, a Chinese Twitter-like service, after he discovered that his son had become the target of malign comments that amounted to cyber-bullying.

Online rumors claimed that Chaw's 6-year-old son, Joe, had deliberately pushed 5-year-old Feynman Ng Chun-yu down a flight of stairs during the shooting of Dad, Where Are We Going? in 2014. Ng Chun-yu, the son of Hong Kong actor Francis Ng Chun-yu and now age 7, sustained an eye injury that could affect his vision permanently.

Chaw furiously denied the allegations. "Let me clarify. My son did not hurt Feynman. If my son was the one who injured Feynmen, I will bear all responsibility. Such accidents are unexpected, but why do my son and I have to endure all (the) scolding and humiliation? I also feel sorry for all of the kids (on the show). Since last year, every one of them has been scolded and insulted by netizens. Enough!" he wrote on his Weibo account shortly before abandoning the platform.

Francis Ng Chun-yu claimed that Hunan TV failed to ensure his son's safety, and later reached a settlement with the company over the injury.

Desire for attention

Another potential problem is that the young participants often become demanding and attention-seeking after being showered with compliments because they have been on TV.

"Some of the children become so accustomed to the camera that they need affirmation," Liu, the education professor, said. "The camera will no longer be there to shine a light on them, even though that light was never authentic, so they are going to seek other ways of gaining fulfillment."

Tian Liang, the former diver who is now an actor, admitted that the exposure his daughter gained by being on Dad, Where Are We Going? had affected her and complained that she now prefers taking part in publicity activities to going to school.

Liu said that despite their name, reality shows don't actually show life as it really is. "Reality TV has a good purpose - to show loving families - and that can be a good thing for children, but we didn't see any benefits for the kids who participated because the shows are scripted and every incident is carefully planned."

He suggested that the new regulations might be a good way of cooling the passions of some parents who take their children to acting classes so they can appear on television and become famous.

Zhuang Yuxin, a deputy professor at the Beijing Film Academy, said short-term fame does not help pave the way if children want to work in the performing arts or entertainment industry. Rather than imposing a "one-policy-fits-all" ban on reality shows, the policymakers should have designed the guidelines to ensure that children are fully protected irrespective of where they work in the entertainment industry.

"It doesn't make sense to completely ban children from appearing on TV, but we do need some guidance to make sure that they are also protected if they appear in other types of entertainment programs and in movies," he said.

"That will be another issue on the protection of child labor, and it seems that there are very few good experiences in other countries we can learn from," he added.

"Until more specific rules are released, everything - including whether and when to step into the entertainment industry - is up to the parents. They should shoulder their parental responsibilities when their kids are exposed to the camera," he said.

Contact the writer at wangyanfei@chinadaily.com.cn

Early fame: A blessing or a curse?

In 2014, Shi Ningjie participated in Deformation Plan, a reality TV show where urban and rural children swap places. As far as he is concerned, neither his personality nor lifestyle changed when he became a celebrity.

In the eyes of the show's producers, the 18-year-old was the perfect participant, the sort of person they had been searching for; a non-conformist. Shi has led a life of privilege - he was born into a wealthy family in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province - but he dropped out of school at 15, and took up smoking and going to nightclubs, even though he was under age.

He was offered the chance to swap roles with Wang Honglin, an 11-year-old girl, who has lived with her grandparents in Shaanxi province since her parents divorced. When the program ended, Wang returned to her isolated village and obscurity.

In 2008, Shi told his mother that he saw no reason to go to school because he planned to become famous, so he was ecstatic when the producers chose him for the show.

Under instruction, he completed a number of tasks, including chopping firewood and visiting people disabled in mining accidents in Baxian, a village in Ankang city, Shaanxi, whose injuries mean they are unable to make a living.

Although Shi did actually become famous as a result of appearing on the program - the number of followers on his micro blog soared to 100,000 - he kept his old lifestyle and little changed. When the program ended, Shi enrolled at a music high school in Beijing, but dropped out a year later. He has been unemployed since then.

"I felt I was a little more mature, but I didn't see too many other differences. I think it's the same for the other participants on the show," he said.

|

Actor Lu Yi (back row fromleft), actor Huang Lei, Olympic gymnast YangWei and singer Gary Chaw watch their children interact with TV show host Li Rui during amedia briefing for the movieDad,Where AreWe Going? in Beijing on Nov 25, 2014. The filmwas a spinoff of a popular Chinese reality TV show of the same name. Jiang Dong/ China Daily |

|

Children and host Li Rui dress as cavemen during the third season of the reality TV show Dad, Where Are We Going? in October. |

|

Zhang Yuexuan, an 8yearold reality TV star, lies in the arms of his father, model and actor Zhang Liang, during a publicity event in Beijing on Dec 24, 2013. Provided To China Daily And Jiang Dong / China Daily |

(China Daily 05/06/2016 page6)

Today's Top News

Campaign spreads Chinese cooking in the UK

Trump to aim all guns at Hillary Clinton

Labour set to take London after bitter campaign

Labour candidate favourite for London mayor

Fossil footprints bring dinosaurs to life

Buffett optimistic on China's economic transition

Hawking answers old Chinese philosophical question

Running the world

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|