'Baby biochips' set to tackle nation's infertility problem

Updated: 2016-04-28 08:40

By Yang Wanli(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

New-generation technology could boost the chances of conception for infertile couples, and aid the government's plans to expand the population, as Yang Wanli reports.

When China relaxed its four-decade family planning policy in January to allow all couples to have a second child, population experts confidently predicted a massive baby boom over the next few years.

However, that may not happen because a rise in the infertility rate among people of optimum reproductive age is likely to pose an obstacle to the government's plans to increase the size of the average family.

In 2014, Li Rui, who has been married for three years, discovered that she and her husband are unlikely to conceive naturally, although they still don't know why.

"I never thought it would be such a long slog to have a baby. I read an article in Scientific American that said about 150 babies are born around the world every single minute. Sadly, none of them is mine," she said.

In the past year, the 32-year-old Beijing resident has tried artificial insemination several times, but has been unable to get pregnant.

Now Li and her husband are considering in vitro fertilization, which may be their last chance to have a child.

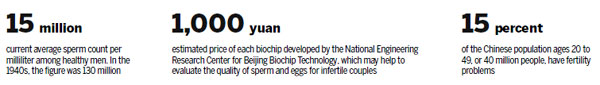

Infertility affects at least about 15 percent of the Chinese population ages 20 to 49, or 40 million people. One in eight couples cannot conceive naturally, according to a report published in January by Woyaoyun, a website jointly operated by the China Sexology Association and the Chinese Medical Association's andrology department, which focuses on male reproductive health issues.

Based on cases nationwide, the report says the infertility rate has risen 10 times since the early 1970s.

However, the scenario may be worse that thought. Wu Jingchun, former deputy director of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, estimated that 25 percent is a more accurate estimate of the infertility rate. "The number is still rising. A birth crisis is approaching," she said.

Twenty kilometers from Beijing's downtown, scientists at the National Engineering Research Center of Beijing Biochip Technology, which made the biochips, are attempting to use bioscience to avert the potential crisis.

They hope that three recently developed biochips - mini-laboratories that can run several tests at the same time - will bring hope to infertile couples via human-assisted reproductive technology.

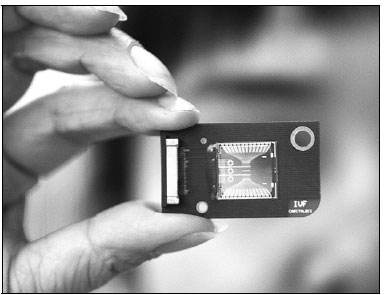

The development process has now ended and the biochips, each no bigger than the palm of a 6-month-old baby, will undergo clinical testing in the near future, according to Xing Wanli, the center's deputy director and also vice-president of CapitalBio Corp in Beijing.

Two of the biochips have been designed to test and evaluate the quality of sperm, while the other checks that the eggs are in the best position to be fertilized. "Trials conducted on mice indicate that the biochips work successfully," Xing said.

"We haven't used any costly materials in them. If they can be manufactured on a large scale for clinical use, the price of each one is expected to be within 1,000 yuan ($154)," she said.

"We hope to separate a single test - such as the one to assess the movement of sperm - from the biochip that tests the quality of sperm and embed it in a portable device, similar to a pregnancy testing kit. People only need to collect a few drops of semen. The method is as simple as the pregnancy testing kit," she said.

Unlike biochips that require a specific power supply, the three new biochips can be used in any lab. Patients only need to provide samples to the medical professionals.

The samples are carried to the biochip via a pipette - a tool used for liquid transportation in chemistry, biology and medicine.

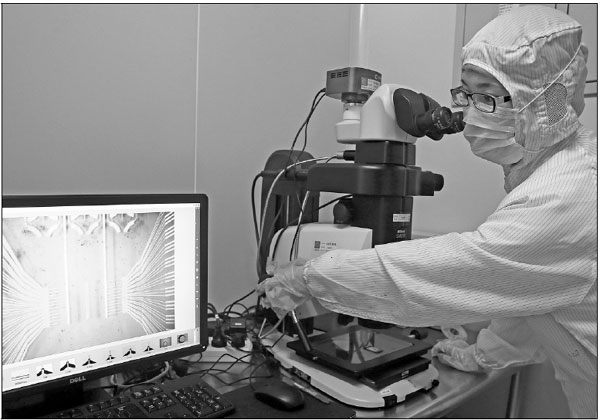

Once in the biochip, the activity of the sperm and eggs can be studied through a microscope to provide a clear picture of the interaction.

Quality, not quantity

Because most healthy men can produce large amounts of sperm - 1 milliliter of semen contains more than 15 million sperm on average - the quality attracts less attention than problems related to human eggs.

However, clinical research shows another side to the story.

Peking University Third Hospital - the country's leading center for infertility problems - studied notes collected between 2004 and 2008 about more than 50,000 cases.

The results of the research indicated that the proportion of viable sperm in each milliliter of semen declined from 47.27 percent to 32.97 percent over the four-year period.

Moreover, the number of patients with a negligible sperm count rose from 6 to 10 percent, while those with a low sperm count rose from 60 to 85 percent during the same period.

Last year, more than 125,000 patients attended the hospital's andrology department. The number was six times higher than in 2009, and about 50 percent of the patients had infertility problems. "After the relaxation of the family planning policy, the number of patient visits has climbed by nearly 30 percent," said Jiang Hui, the director of the department.

"More men are facing fertility problems, despite a rise in the number of medical staff available to treat them, and people's increasing awareness of reproductive health," Jiang said. "A number of factors are to blame, including environmental pollution and the pressure of work."

Three basic tests

The fusion of a sperm and an egg is the beginning of human life. The health of sperms and eggs is equally important, irrespective of whether the child is conceived via natural conception or through the use of human-assisted reproductive technologies.

In most public hospitals, sperm testing and evaluation mainly focus on three basic functions: sperm count, motility (the sperm's ability to move), and morphology (the shape and appearance of the sperm).

The development of medical science has resulted in the discovery of a wide range of factors that determine whether a sperm can find the egg and swim in the right direction to achieve a successful union.

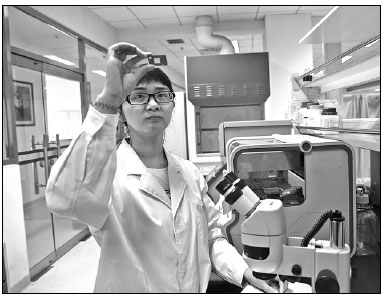

"The uterus is like a big maze. To swim from the vagina to the fallopian tubes and find the egg is never a coincidence," said Xie Lan, a researcher at Tsinghua University who led the design of the biochips. "In the process, the sperm's chemotaxis (the movement of organisms as a reaction to chemical stimulus) and thermotaxis (movement of an organism toward or away from heat sources) are the other two major factors."

Xie said human eggs release a chemoattractant, a chemical that signals their position to sperm, while the difference in temperature between the cooler sperm reservoir and the warmer fertilization site also prompts the sperm to swim in the right direction.

"Clinical assessment of the two indexes is currently lacking. We constructed two micro-devices with channels shaped like the system inside the female reproductive tract. Sperm are permitted to swim freely without any coercive force, so they can be tested without damaging them," she said.

Motility and chemotaxis are tested on one biochip. Motile sperm will be the first to arrive at the end of a straight "running channel", which is connected by two sub-channels to test the sperms' response to various concentrations of chemoattractant.

Thermotaxic evaluation is undertaken on a second biochip. Temperature-sensitive sperm are attracted to the sub-channel with a high temperature setting, while non-responsive sperm are evenly distributed across the two sub-channels.

In the two tests, about 10 percent of motile sperm were found to be chemotactically responsive, while 5.7 to 10.6 percent showed a thermotactic response.

Experiments have yet to be conducted to establish the number of responsive sperm in both tests.

"But the number might be low, between 5 to 10 percent. The tests can possibly explain some unknown problems with pregnancy, and contribute to sperm selection for IVF," Xie said, adding that work is underway to try and combine all three tests on one biochip.

Implantation screening

Many couples who need IVF technology, such as Li and her husband, say they don't just want a "test-tube" baby, but also a genetically healthy one.

"About 20 percent of infertile patients who want a baby have to turn to IVF. Since the process is more invasive and costly, we need to choose the best-fertilized eggs for implantation," said Qiao Jie, president of Peking University Third Hospital, where more than 5,000 test-tube babies were born last year.

About 10 eggs are fertilized simultaneously in the hospital's lab, according to Qiao. When the fertilized eggs developed into a blastula - a hollow sphere of cells - doctors choose one or more cells for genetic screening, a process known as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. If a blastula passes screening, it will be placed on a waiting list for implantation.

Under the current procedure, eggs are kept in liquid and can swim freely, which makes it difficult to monitor them every day. However, on the biochip, each egg is positioned undamaged and the channels on the biochip allow the sperm to meet the egg naturally.

"The technology has not been tested on humans. But if it completes the clinical tests successfully, it will make future study of IVF technology far more convenient," Qiao said. "It follows the trend of 'precision medicine' - an approach that allows doctors and researchers to more accurately predict which treatments and prevention strategies for specific illnesses will work in which groups of people."

According to Xie, the next research program will focus on trying to build a biomimetic uterus, which can mimic biochemical processes and, therefore, support the growth of human embryos.

"It may even mean that in the future, a baby may be born without a mother. Human assisted-reproduction technology is moving forward rapidly, and that's expected to bring greater benefits to the next generation," she said.

Contact the writer at yangwanli@chinadaily.com.cn

Sperm counts on downward spiral

Average sperm counts in China have been falling for more than 60 years. In the 1940s, the average among healthy men was 130 million sperm per milliliter, but the number has fallen consistently since then, according to Jiang Hui, deputy director of the Center of Human-Assisted Reproductive Technologies.

"The decline in the sperm count has not just been witnessed in China, but in most countries," Jiang said, adding that the World Health Organization has updated the global standard of sperm counts. Under the WHO's standards, sperm counts of about 60 million per ml were considered normal in 1989, but by 2006, the number had fallen to 20 million. It's still falling.

"Now, it's 15 million," Jiang said, attributing the decline to a wide range of causes, including environmental pollution, lifestyle changes, people taking less exercise and increased work stress. A couple is considered to be infertile if there are no signs of pregnancy after a year of unprotected intercourse, according to Jiang.

He said 40 percent of infertility cases are due to problems with men, and 40 percent due to problems with women. The causes of the remaining 20 percent are unknown.

Evaluation of the male factor involves a semen analysis, a post-coital test (conducted 6 to 12 hours after intercourse to detect the presence of sperm in the woman's cervical mucus) and hormonal determinations of the level of testosterone.

A normal semen analysis requires a volume of 2-to-5 ml, and the semen is considered to be healthy if it shows more than 15 million sperm per ml and they have a mobility range of more than 50 percent.

|

A biochip developed by the National Engineering Research Center for Beijing Biochip Technology can evaluate the quality of sperms and eggs. Zou Hong / China Daily |

|

Researcher Xie Lan, chief biochip designer, checks a biochip at the development center in Beijing. Zou Hong / China Daily |

|

|

(China Daily 04/28/2016 page5)

Today's Top News

Beijing least affordable city in the world to rent

US accused of 'hyping up' military flights

Banks offer passport to integration

Obama casts doubt on post-EU deal

Chinese runners flood London for marathon

Chinese philanthropists explore British way of 'giving'

Back on the up

China leads way on US adoptions

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|