Love affair with the city ending marriages

Updated: 2016-03-28 07:54

By Zhou Wenting(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

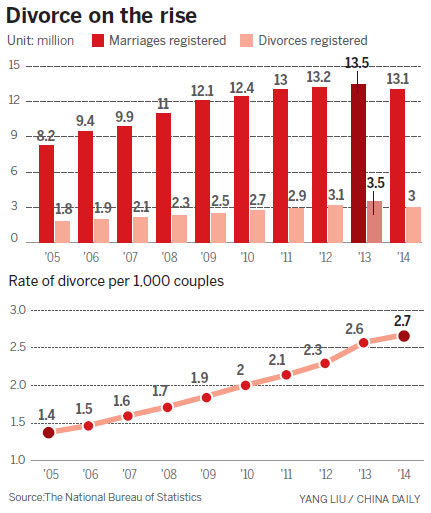

Rural women are getting divorced in record numbers, something observers say is due to the empowerment and experience they acquire when working far from home. Zhou Wenting reports from Shanghai.

A record number of women from rural China are filing for divorce. In most cases, their marriages broke down after they migrated to the city in search of work but found love or self-empowerment instead.

Guo Feifei is among them.

After leaving home in rural Anhui province as a 21-year-old to work at an electronics factory in Shanghai in 2010, she ended up realizing she no longer wanted to remain married to the man she wed from a neighboring village back home.

She drew a line under her five-year marriage two years ago.

"I blamed myself when the idea of divorce first occurred to me, and I questioned myself repeatedly about whether leaving home for work was a good idea," said Guo, a native of Anhui. "But, eventually, I realized I was renewed by city life and I had found myself living in a different world from my ex-husband."

Statistics from the people's court in Songzi city, Hubei province, are typical. They show that three in four of the more than 700 divorce lawsuits filed there in 2014 were initiated by wives, and more than 90 percent of those involved women who had migrated to big cities for work - and often husbands who stayed behind in the village.

Shi Renbing, head of the Population Research Institute at Wuhan-based Huazhong University of Science and Technology, said in a report examing the phenomenon that similar patterns were being played out in rural regions of Henan and Sichuan provinces as well.

Sociologists believe the women get new experiences in the cities they move to and an economic independence that means many of them start to pay more attention to their own wellbeing and aspirations than they had ever done before.

"Usually, rural women are deprived of the right to make choices and decisions, starting in their childhoods," said Lin Zi, founder of a psychological consultancy in Shanghai.

"When they enter an open environment in a leading city, their self-awareness and inner power explode to push them to make changes," Lin said.

"It seems as if this phenomenon is not just about marriage but is really about choosing who they want to be."

In the case of Guo, she grew up with two younger brothers, who were favored by her parents: It was the boys who usually got most of the attention from the extended family, both in terms of finance and love, she said.

"One of my brothers and I suffered from asthma in childhood. I was often pinched by my mother when I could not stop myself coughing at night but my brother always escaped that," she said.

Guo believes that women are treated as inferior in rural areas, especially the most economically disadvantaged places, and she says such thinking is still mainstream.

But that all changed when she went to Shanghai.

Two years after arriving in the city, when she went to work as a nanny, the differences she had begun to notice really hit home.

"After joining Shanghai families, I found that women in big cities can receive a good education and enjoy equal opportunities in many aspects of life, and they can be independent and live a colorful life," she said. "That is totally different to what happened to us - a girl in a rural area is an accessory that is neglected by parents, her husband and the whole family."

The longer she stayed in Shanghai, the less she wanted to return to her old life. Today, she has no intention of leaving.

"I win the trust and favor of my employers and I can earn as much as a college graduate if I work hard. I'm satisfied with my life here," she said.

Guo's ex-husband used to say the option of going to the city and earning good money wasn't open to him because there were no suitable jobs but Guo believes he could have made a go of city life if he had been willing to take on tough jobs, such as those in the construction field or even by working as a courier. She feels as if she had more get-up-and-go than he did. Academics tend to agree.

"Women, who are used to receiving less care from the family and fighting for opportunities by themselves since childhood are more independent and proactive when it comes to work," said Xue Yali, a researcher with the Family Research Center under the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

But Lin added that, despite the difference in attitude, the type of work that migrant women can find does make it easier for them to integrate into city life.

"Men are mainly involved in heavy industries and work hard and often feel isolated and so many often can't wait to return home as soon as possible," she said. "However, women in many cases participate in housekeeping, which is not as grueling, and it also gives them a chance to see the real life of local families and they want to be a part of that."

Guo's ex-husband, meanwhile, thinks their problems lay in the fact that his wife was too ambitious and aggressive.

"We lived a life that was above average in our village but she was unsatisfied," he said. "I wanted a woman to take care of the family rather than have an adventure outside."

Multiple factors

Such breakups are often the result of many things going wrong over a long period of time. Marriage breakdowns can involve violence, both physical and verbal, and economic control, said Chen Yandi, founder of Hand-In-Hand, a non-governmental organization dedicated to protecting the rights of female workers in Shenzhen, Guangdong province.

Qiu Yan from rural Jiangsu province tied the knot with her ex-husband in 2006 at the age of 22. Not long after the marriage, her introverted partner became addicted to gambling and Qiu said she endured his beatings when he lost.

"Moreover, my mother-in-law's attitude toward me was as if she was venting all her spite from decades of bitterness that she had got from being bullied by her own mother-in-law. That home was like a prison for me," said Qiu.

She, too, went to Shanghai and worked in a hotel while her husband drove an illegal cab in Nanjing.

While working at the hotel, she drew the attention of a security guard who also worked there and the couple hit it off and eventually began dating.

Lin, the consultant, said many women strongly desire independence and freedom from abusive relationships once given the chance to change their lives.

"They believe whatever the new life will be like, it won't be worse than the previous one," Lin said.

Qiu divorced her ex-husband in 2012 and moved in with her new partner.

"In rural regions, usually we don't have the right to choose our marriages, so, when they end, the relationship collapses more easily," Qiu said.

Easy option

Xiao Xue (not her real name) grew up in a rural area in Chongqing municipality where she was engaged to a man her own age.

She never dreamed she would be bold enough to end their engagement, but Xiao left home for Guangzhou at age 18 in 2008 and worked as a waitress in a karaoke bar.

She loved the glitzy city life and, when her mother died in an accident, she felt as if there was no reason to leave the city.

"There was nothing left that made me want to return to the village," she said. Instead, she met the owner of a barbershop and began working there.

"He was 20 years older than me and he was divorced," said Xiao.

She said she saw the prospect of marrying the barber as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to change her destiny and leave the countryside forever.

"Everybody pursues a better life and the nation is advocating the urbanization of the rural areas. Why wouldn't I stay in the city?" said Xiao, who got married last year and became manager of the barbershop.

For many without the option of improving themselves through education, marriage is seen as a fast-track way for women to secure their place in the city. Traditionally in China, women seek a man with a higher social standing than themselves anyway, so finding a husband in the city seems to fit with that, sociologists say.

But marrying or remarrying is far from a perfect route to hanging on to the city life.

"It will take someone at least 10 years to obtain a permanent residence permit for a big city like Beijing or Shanghai, which means women will not be able to gain equal access to social welfare as other citizens within this period," Xue, the researcher, said. "And in the meantime, there are abundant variables in a marriage during those 10 years."

She said that women who stay in the rural areas and find ways to be fully involved in the running of their families and in the upbringing of their children will earn the respect of their families.

Social experts point out that the flow of women out of rural areas and into the big cities and the resulting pressures that the migration puts on marriages will not dry up until the underlying issue - the urban-rural divide - is addressed.

Contact the writer at zhouwenting@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 03/28/2016 page6)

Today's Top News

President optimistic for Sino-German cooperation

Info sharing 'is key' as Europe faces terror threat

Uneasy times as Belgium mourns the dead

Belgian bombing suspect still at large: Prosecutor

Belgian media withdraws reports of suspect's arrest

Brussels bombers were brothers El Bakraoui

Chinese citizens in Belgium get help after attack

Europe ramps up security in wake of Brussels attacks

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|