A small person's big identity question

Updated: 2014-05-30 07:12

By Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

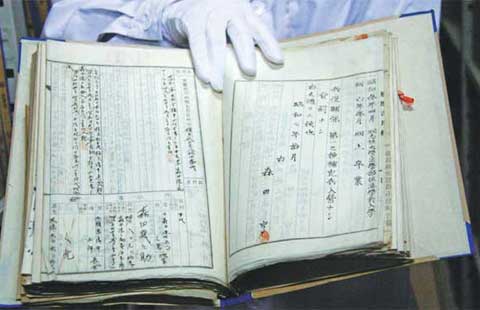

[Photo by Erik Nilsson/China Daily] |

Will teachers also fawn over, spoil and hold to different standards this girl who speaks Chinese and thinks mostly like a native but bears a conspicuously different visage? Will other kids resent that or reject her because of her appearance?

Will they, seemingly more likely, play with her and consider her a friend who's like, but not really one of them? Or, will nobody think of it after a few seconds since she speaks and acts like anyone else born and raised in Beijing, even when she's an adult?

I have many American-born Chinese friends who've started lives in Beijing to divine their identities. We wonder if Lily might someday do the same in reverse since our family is in China indefinitely.

That said, our ABC friends were considered Americans in that country while growing up. But China is different. It's virtually impossible to "become Chinese." China is typically tolerant of foreigners by virtue of recognizing their different backgrounds according to a relativistic outlook.

While different ethnicities and nationalities may perhaps categorically be considered foreigners, they're essentially accepted in society, yet as such.

Still, foreigners with Chinese characteristics are often most welcomed.

The majority of Americans believe foreigners become American if they're born in the United States or live in the country for a long time and, most importantly, "act American" - whatever that means. This hails from a history as an immigrant nation.

Studies show so-called third-culture kids, raised outside their parents' homelands, are more likely to get along with other third-culture children than with peers from the cultures in which they or their parents grew up.

According to this perspective, Lily and kids like her will be able to better relate to a person raised by a Zambian mother and Columbian father in France than her American cousins or Chinese classmates.

That's not to say she won't get along with anyone from anywhere. The studies simply suggest an affinity constructed by a common third-culture upbringing. And third-culture kinship is just a rule of thumb. In a complex and globalizing world, integration means more third-culture kids.

Ultimately, Lily, China and the world will decide her identity - and that of other children also in her still small but no longer tiny shoes, in a big country in a big world.

Related Stories

As a foreigner, what to do if you have a sudden medical emergency in China? 2013-11-28 11:08

Passionate judge learns from handling foreigner-related cases 2013-06-19 15:18

Time to accept I'm forever a foreigner in Zhengzhou 2012-01-05 10:31

Chinese attire and cultural identity 2014-03-25 11:01

An entity of identity 2013-12-12 10:28

Today's Top News

Relatives of MH370 passengers angry at search progress

European firms' 'best era' may be over in China

Russia troops 'leave' Ukraine border

Everest climber denies accusations

A small person's big identity question

Rebels down Ukrainian military helicopter, killing 14 troops

Russia bans 'historically false' WWII movie

Egypt extends presidential vote

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|