Herders hope for greener pastures

Updated: 2012-07-12 09:21

By Cui Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Bid to preserve grassland shows seeds of success, Cui Jia reports from Hami prefecture, the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

Riding high in the saddle, Stek Ajey whistled and cajoled his flock of 84 sheep.

He counted the animals - his only source of income - meticulously, as if they were his children. The 59-year-old member of the Kazak ethnic group, who has been a herdsman since he was 17, was preparing to move his entire flock from the spring grazing lands to summer pastures on the far side of Tianshan Mountains in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

This is the first time that Ajey moved his flock in accordance with a strict schedule, a practice aimed at reversing environmental damage wrought on the grassland and preventing further depletion.

China has about 400 million hectares of natural grassland, the second largest in the world in terms of area, but climate change, excessive grazing and rural development have damaged 90 percent of that land.

|

|

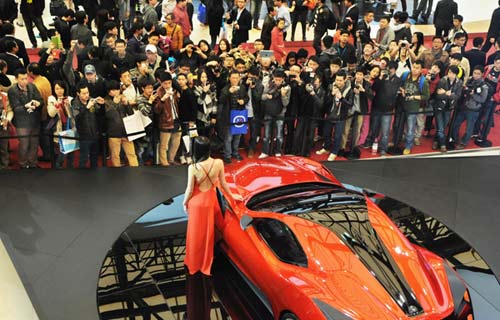

Herdsmen in Yiwu county, Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, have their hands full as they try to load sheep onto a truck and move them to summer pastures. Zhang Wei / China Daily |

"We are now allowed a set number of days we can stay on the different seasonal grassland. That's to make sure the land has enough time to recover," said Ajey of Yiwu county in Hami prefecture. However, the idea of a schedule is still something of an alien concept.

"As a nomadic herdsman, I am used to deciding when to move my herd according to weather conditions and, of course, my mood," he admitted.

Along with 3,200 other herdsmen in his hometown of Qianshan, Ajey signed a grassland protection agreement with the local government last year.

The agreement is part of a subsidy and reward program instigated by the government for herdsmen in eight regions and provinces: Xinjiang, the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, the Tibet autonomous region, the Ningxia Hui autonomous region and the provinces of Yunnan, Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu.

The budget for the program was 13.4 billion yuan ($2.1 billion) in 2011, the largest of its kind for more than 60 years in terms of funding and coverage, according to Xie Xuren, the minister of finance. The agreement detailed the boundaries of the grassland assigned to each herdsman and the areas where grazing is strictly prohibited. The agreement also stipulated that each family member in Qianshan is only allowed to keep a maximum of 20 sheep on the grassland, while the other animals will be housed in sheds.

"Look. We are not allowed to go into the fenced area," said Ajey, while directing his herd away from the prohibited land. Around 60 percent of the 529,300 hectares of grassland in Yiwu county are now under protection. "Actually, part of the prohibited area is where I used to graze my flock, so I receive a subsidy of 2,400 yuan every year," he said.

Ajey has a family of five and owns 167 hectares of natural grassland. If he can keep his herd below 100 head, he will receive an annual subsidy of 22.50 yuan per hectare. "Many herdsmen have complained that the subsidy is too low, compared with the price of sheep," he said. "My sheep can sell for 1,000 yuan each, so I'd rather raise more sheep than receive the money."

On a Monday morning in May, the office of the township committee was packed with herdsmen who'd left their horses tethered impatiently outside. This is the first year that Qianshan residents have received the subsidy and those from Shimogou village, which lies within its jurisdiction, were selected to be the first to get the cash.

After checking the figures on his agreement, Islamhan Ohar rubbed his finger on an inkpad and left a print on the paper. Along with a formal signature, this is the accepted method of ratifying documents in the Kazak culture. "The money won't make up for the losses," sighed the 46-year-old herdsman. Ohar owns more than 120 sheep, but as his family only consists of three members some of his flock will have to be housed in the communal sheds. Moreover, almost one-third of his former grazing land now lies within the prohibited zone.

"I don't own any sheds and even if I did, I would need money to buy fodder. I don't think the subsidy could cover the cost," he said. The program also offers an annual subsidy of 500 yuan to help households purchase diesel oil and animal feed.

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|