Lhasa memories etched in ink

Updated: 2011-04-20 07:55

By Feng Xin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

Huang Jialin, a Han artist born in the Tibet autonomous region, poses in front of an unfinished painting of the Potala Palace. Wang Jing / China Daily |

For video of the artist: The color of soy sauce

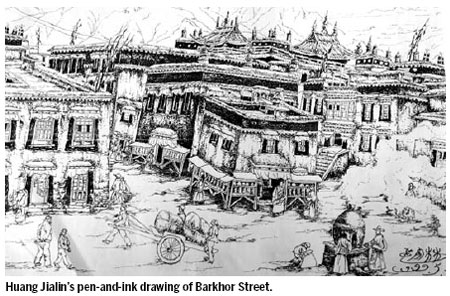

One man's love of Lhasa's Barkhor Street fuels a voracious appetite for pen-and-ink drawings of its ancient buildings. Feng Xin reports.

"The color of soy sauce,"says Tibetan-born artist Huang Jialin when he is asked to pick one hue to describe the playground of his youth - the 1,300-year-old Barkhor Street in Lhasa, capital of Tibet autonomous region. Huang, 45, trawled its length as a petty thief and odd-jobs man in his teenage years, before he began knocking on doors to measure every house on the street.

In 1996, he was tasked with making line sketches of Barkhor Street for an international non-profit organization as part of its efforts to protect the ancient street.

The nearly kilometer-long Barkhor Street circles Jokhang Temple, a center of worship for Tibetan Buddhists. For followers, who believe in reincarnation, the street that has no entrance or exit is a metaphor for life itself, sans beginning or end. As one of the most important prayer routes, tens of thousands of Tibetan Buddhists crowd to the street every day.

"The old houses on Barkhor Street were all painted in lime white back then," Huang says, recalling that every year people went onto the roofs and repainted their houses to welcome the gods. "The paint left dark stains, layers of it," Huang says.

An ethnic Han, Huang was born in Tibet's Nyingchi prefecture after his parents moved from Chongqing in the 1950s and is more fluent in Tibetan than in Mandarin.

Huang's formal education ended with elementary school, and his family moved to Lhasa when he was a teenager. He enjoyed hanging out on the street all day with his Tibetan friends, picking up small carpentry jobs now and then.

If a painting class, the first of its kind in Tibet, hadn't started in 1982 and actively scouted students, he would probably have never picked up a brush, Huang says.

"I would have been in and out of jail three times by now," he jokes.

Although the class lasted only three months, Huang says he felt like a proper artist at the end of it. He put on clothes with paint stains and wandered around Barkhor Street, "just like an artist".

Huang found his first learning opportunities on the street, watching Tibetans make thangka paintings with mineral paints. He pretended he didn't understand a word of Tibetan, so he could watch them hard at work. Only when he got to know them better did he talk to them in Tibetan.

"They were all very surprised and asked, 'How come you speak the Lhasa dialect so well?'" Huang says.

Being able to speak Tibetan helped Huang again when he was asked to copy the ancient wall paintings inside Jokhang Temple, four years later. His teachers were the source of a wealth of information not just about the paintings but also about Tibetan culture, and Huang soon struck up a good relationship with the monks.

Despite his love of painting, Huang found it was difficult to survive on it. By the mid-1990s, taxis began filling the streets of Lhasa, and Huang became one of the first taxi drivers in the city - without a license, he says.

"I didn't pen a single stroke for three years," Huang says. "Those three years were really painful."

Not until 1996 did Huang finally get paid to do what he liked. A friend found work for him at a German-based nonprofit organization that works to protect ancient cities around the world.

Authorized by the local government, Huang was asked to measure every house on Barkhor Street - the height, width, thickness of the walls, type of construction and even the number of windows and pillars. He then transferred all this information into his ink sketches.

This assignment lasted three years.

"Everyone had a story," Huang says, adding he was never refused entry into the homes on Barkhor Street, thanks to his felicity with Tibetans and his knowledge of the local culture. "If you live in Tibet, you have to learn to be respectful and modest."

Measuring every house on the Barkhor Street enabled him to observe and commit to memory every detail of Tibetan architecture. It also laid a solid foundation for Huang's pen-and-ink drawings, which went on to become famous nationwide.

He then traveled to every prefecture of Tibet by foot, on bicycle or by hitchhiking, to paint. In 1999, he decided to move to Chokpri, a mountain that stands opposite the Potala Palace in Lhasa - a Tibetan landmark.

"I couldn't stand seeing people litter on Chokpri," Huang says. So he applied to volunteer with the Lhasa Landscaping Bureau. He spent three years picking up the litter on the mountain while painting the Potala Palace.

"I drew the Potala Palace in each of the four seasons, in the morning and evening, in different light conditions, and in rain and snow," Huang says.

After making 50 different paintings of Potala Palace, Huang finally came up with one in which the landmark is surrounded by flaming clouds that many said reminded them of the scene depicting the end of the world in the film 2012.

Despite earning acclaim and traveling far and wide, Huang says he always returns to Barkhor Street. He has a strong attachment to Jokhang Temple, where he spent so much time sunbathing on its roof or simply sitting against a pillar.

"I always tried to revive that spirit of Jokhang Temple," Huang says. "Especially when I felt frustrated, I just walked into those old houses, savored a pot of sweet milk tea."

But he no longer goes in there, he says. "Now you can't get into Jokhang Temple without buying a ticket," he says. "And if you sit there, you will find 10 tour guides telling 10 different versions of a story. They are loud and shameless. They make me want to hit them."

His disappointment finally made him move his art studio from Barkhor Street several years ago. "Modern civilization is like a piece of film. It wraps around an older civilization and gradually suffocates it," he says.