Martial arts clubs hope to hit profit

Updated: 2011-03-23 07:59

By Chen Limin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Groups find it hard to stand on their own, reports Chen Limin in Foshan.

Lun Zhixiong likes to have a cup of tea as he chats with practitioners of kungfu. Sometimes he communicates not just with words but also through the stylistic body language of martial arts.

They have been part of his daily routine since he opened a martial arts club with several of his friends, fellow disciples, in Foshan. It is the ancestral home of Wing Chun, a style of martial arts renowned for techniques executed in a seemingly relaxed manner.

Lun, now in his 50s, started learning Wing Chun in his childhood and, along with many others, set up martial arts clubs in the city, but it's a bittersweet endeavor. While the popularity of martial arts has soared, few clubs make a profit. Can commercialism turn that around?

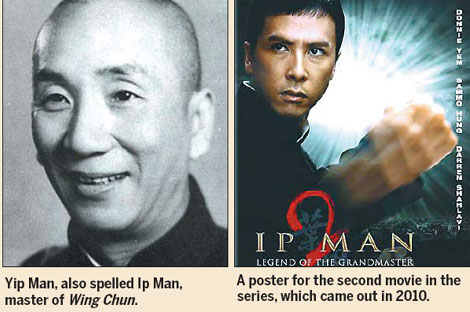

Foshan now has 200 clubs devoted to martial arts, their appeal boosted largely by a series of movies based on the life of Yip Man, a Wing Chun master born in the late 19th century. The first movie was released in 2008; two others came out last year.

More than 20 Wing Chun clubs have been set up in Foshan since 2008, bringing the total to 87, according to Xue Mianben, president of Foshan Martial Arts Association.

Despite the increasing popularity of Wing Chun, and kungfu as a whole, a martial arts club turns out not to be a good revenue generator.

"It will be very impressive if we can make ends meet with the little earning we get from training," said Wu Guojian, a Wing Chun master with Foshan Pengnan Wing Chun Association, one of the largest Wing Chun clubs in the city.

| ||||

The club has held summer camps for the past four years, training about 1,000 learners, and it has 150 members who practice Wing Chun regularly and pay about 800 yuan ($122) a year for training. However, the routine expenses of electricity, water and masters' salaries render the training fees far less than needed to produce a profit.

"We have to pay out of our own pockets sometimes when we go out for contests or martial arts shows," Wu said. Running a club "is not for money, but interest".

Wu's club received financial support from He Liubo, a fellow Wing Chun disciple who runs a gas station. He invested 180 million yuan to build the club in 2007. Most of the clubs in Foshan don't have such sponsors.

|

These men, who wear business suits in daytime and kungfu shirts at night for practice, don't expect the clubs to be what they cash in on. Overseas clubs, however, have developed in a completely different way.

Overseas success

"Running a club in a foreign country is very practical. Business is business," said Liang Dongsheng, a kungfu master from Foshan who has been teaching Wing Chun in Mauritius since 1984.

He said one hour of training in Wing Chun can cost as much as 25 euros ($35) in France, although the rate is lower in less developed countries.

Liang's operation is basically a karate club, but it also provides Wing Chun courses and services ranging from Chinese bone-setting methods to acupuncture. For important occasions, such as the Chinese Spring Festival, he usually leads a team in performing the traditional lion dance to generate income.

He believes that diversifying a martial arts club's services and operating it in a businesslike way are keys to success.

Teaching martial arts "will not last long without an economic basis", he said. "Take Shaolin Temple, for example. Although some people think it's against tradition, it has kept pace with times and developed very well, at least by appearances."

The Buddhist temple, known for its kungfu and qigong practices in central China's Henan province, has sparked controversies with every commercialized step it takes, such as establishing a restaurant and medicine company and shooting movies about itself. Its abbot, Shi Yongxin, who holds a master's degree in business administration, is praised for his aggressive business endeavors and criticized for leading the temple too far in commercialization.

In Foshan, the martial arts are not related to religion, but some masters fear commercialized operations may change Wing Chun teaching, which is based on a master-disciple relationship rather than production-line teaching.

Other masters see commercialization as a means to sustainably develop the martial arts.

"It will surely be good to combine martial arts and commerce as it's a way to make something big," said Hu Chongpin, a master with Nanquan Development Center. Foshan is a center for some 50 kinds of nanquan, Chinese boxing styles that originated in South China.

"What we have in television and movies is just a fraction of the rich martial arts resources," Hu said, "and if there are companies that develop movies, sitcoms, books and others based on nanquan stories, this may outshine Shaolin Temple."

But he can't help giving a disappointed sigh. "A single martial arts club is just too small to realize it." And a big change in martial arts' commercialization from the bottom up is not likely to happen without strong support from the government, he said.

"Many of the ideas to develop Foshan's martial arts have ended up in lip service," said Xue Mianben of the Foshan association. Martial arts can't compare with industries that contribute greatly to the economy, he said, so they may seem less important to the government.

"It needs a change in ideas about how to develop the martial arts culture," said Guan Runxiong, president of Nanhai Sports Federation, a semiofficial organization under Nanhai district, Foshan.

The NBA as a model

Guan is responsible for martial arts marketing with the Foshan Sports Bureau. These days, he's busy drawing up an ambitious plan for free-boxing matches in the city.

Inspired by the National Basketball Association in the United States, Nanhai Sports Federation has set up World Kungfu Club League, an association for professional free-boxing players, and is joining with other companies to roll out free-boxing contests. It aims to hold one to two international matches every year, and local ones every week or month.

In the 2009 Sino-Thai Boxing Competitions, matches between China and Thailand held in Foshan, 80 to 90 percent of some 9,000 tickets were sold and 150 million people watched the contest through different media, Guan said.

That's a worthwhile try in commercialized sports and kungfu, he said. "We will let companies invest in the matches, and try commercial operations through ticket sales, advertising and television broadcasting."

Guan said the first thing to do is to grow the market, by advertising heavily and by offering kungfu training courses to develop interest. "It may take five to 10 years to make kungfu into an industry," he said.

Foshan also plans to open its first martial arts school, invested by Sin Kwok-lam, producer of one of the Yip Man movies, among others. It hopes to enroll about 300 students in September, said Yang Zhenfu, director of the Foshan Sports Bureau. Foshan hopes to learn from the city of Dengfeng, where Shaolin Temple is located. Numerous martial arts schools there teach Shaolin kungfu.

"Capital wants to go to martial arts, but it's still not known what the best way is," Yang said. He said that a lack of talent with commercial operations is one of the biggest obstacles to Foshan's developing its martial arts culture into an industry.

"But after a successful example is set," he said, "I think capital will follow."