Prince of eels hits his stride in Beijing

Updated: 2010-11-21 09:21

By Mike Peters (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

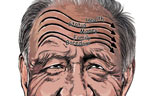

Max Levy's passion for food has taken him from New Orleans to Tokyo to New York to Beijing. [Photo by Jonah Kessel / China Daily] |

Beijing chef Max Levy has had a very long love affair with the fanged fish. Mike Peters follows the slippery trail.

A 15-year-old boy grabs a fat, slimy eel behind the head, and watches wide-eyed as the predatory fish wraps its body tightly around his forearm. Fifteen years later, Max Levy is wide-eyed again as he recalls his fearsome fascination with the freshwater beasts of his native Louisiana.

"There were stories about those eels wrapping around people's necks and strangling them. I don't really know if they were true," he says. "But those eels were really strong."

| ||||

"The distinct taste of the eel once more demonstrated Chef Levy's ability to create endless variations out of very basic and pure material," Time Out magazine ogled as it anointed the New Orleans-born New Yorker as Beijing's best chef for 2010.

"The man can do no wrong as far as eel is concerned," GourmetTraveller.com raved in another review.

The 30-year-old Levy is wary of such accolades, usually bestowed on the sort of old-time chefs who populate films like Who's Killing the Great Chefs of Europe? A man who likes to introduce himself as a cook, not a chef, Levy found himself doing too much, too fast once before.

That was back in 2003, when Levy came to Beijing the first time as the sushi chef in a new restaurant with lots of promise. That kitchen lost its leader, and Levy, then 24, was given the reins as executive chef.

"The food was good," he muses, "but I didn't really have a defined style. I was simply duplicating other people's style." So he went back to New York and went to work in a friend's kitchen, sure he had more to learn.

The return trip made him appreciate an important difference working in the two cities.

"In New York, the suppliers come to you," he says. "You can get any quality you want - even the very best - without leaving your kitchen."

China is a different matter: "You never stop looking for suppliers. And you never stop negotiating, not only for price, but for quality."

Many expats in the food industry here get frustrated by that, he says, and they just find it easier to import the foods they are familiar with.But there is plenty of quality food in China, he insists. "Do you really think these people had a primo civilization for 5,000 years and never ate anything good?"

Levy is not only willing to hunt for suppliers and haggle with them, he'll create them.

"We weren't really happy with the quality of pig we were getting," says Levy. "So we got together with some agriculture professors at Peking University, who helped us teach some nearby farmers to produce pigs in a more natural way."

Levy doesn't buy pieces of meat, he buys whole animals, and he wastes very little. "We use the head to make a terrine - like head cheese, you know - but we don't add gelatin like agar. We cook it down slowly with soy sauce, wine and duck fat, and it just mellows."

Getting the most out of an animal brings us back to eels.

"With most fish you waste about 30 percent," he says. "But with an eel almost everything gets eaten. It has a small digestive system. Small head. One bone. And most of the water stays in the meat."

Levy's clinical approach is an asset in business, and as scientific as it is artistic.

"Artistic," he says, shaking his head as he recalls his days training with chefs in Japan. "That's why a lot of people who want to be sushi chefs will never make it. Making sushi is about repetition and consistency, repetition and consistency." Get those down first, he says, or you'll waste your time trying to an artist.

That attention to basics won him plaudits on the sushi scene of New York, and kept him on the radar of chef entrepreneur David Laris of Shanghai, the consultant for Opposite House who recruited Levy for his current job.

But before he came back to Beijing, Levy went to Japan to learn more about eels. He worked at the eel farm for about three months to see as much of the life cycle as he could. He also spent time raking sea salt, and after studying how the Japanese harvest and make salt, he now enjoys making his own. For that purpose, he orders 20-kilogram boxes of salt water collected from the sea south of Osaka at a depth of about 100 meters.

"It's super salty," the chef says, his face alight with pleasure at how awesome salt can be. "After we filter it, we use it to make tofu, and we use what's left to make sea salt."

Tofu and salt aren't all that Levy and his kitchen team make. They cure their own hams, make their own sausage, brew their own eel sauce, whatever it takes to fill in the gaps between supply and Levy's demand.

Levy approaches the venture he co-owns, the bar and restaurant called Apothecary, with the same single-mindedness.

"Growing up in New Orleans, I was very used to the cocktail culture, though I didn't think of it that way at the time," he says. "My friends and I weren't finding the quality of drinks we wanted except at expensive hotel bars. And we were looking for a different atmosphere, too. At a fancy Japanese hotel, you feel like you are in a temple," he says with a grin. "And at a college bar, the atmosphere is, well, people puking."

So Apothecary was born - a casual place to hang out with good drinks - where Levy's kitchen makes the ice and the tinctures for the bar, plus the Sunday special: what some foodies have rated the best fried chicken in Beijing.

Some online chatter about Apothecary is less flattering, particularly posts about the price of drinks.

"We're putting real liquor in well-made drinks," Levy says. "That costs something. We're still cheaper than drinks of the same quality at a top hotel bar."

I asked the young chef if he has developed other interests during his three years in China outside the world of food.

He pauses, as if stumped by the question.

"Well, a lot of times I work seven days a week"

His face brightens. "I did go to Xiamen for a couple of days with my girlfriend," he says.

A beautiful place, I say.

"Well, we're not really big on natural beauty," he shrugs. "So when we go away, we want to go to places to eat. And where it's warm. So we really went to Xiamen for the oyster omelets," he says happily. "We ate four or five oyster omelets every day."