Committing to China: 5 questions MNCs need to ask

Updated: 2012-09-06 10:59

By Gong Li (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

To get things done, the boss in China often must first get the approval of several regional and business-unit heads.

This kind of bureaucracy slows decision making and can dilute outcomes. Also, country-level performance indicators are often buried in broader Asia Pacific numbers, obscuring both progress and challenges in China.

And with profit-and-loss accounting run at the regional level, China operations must compete with those in other Asia Pacific countries for investment dollars, again reducing the local executive's ability to act quickly and decisively in the market.

Shortening reporting lines can help increase responsiveness in China by speeding up decision making and giving leadership at headquarters a better handle on what's happening on the ground.

Intel, for example, treats the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong as a separate geographic unit; the company's China management reports directly to the head office. Intel's move underscores the importance of China, which in 2011 overtook the United States to become the world's biggest PC market.

3. Is China represented on our leadership team and board of directors?

A recent survey found that only 8 percent of the executives running the China operations of multi-nationals sat on the board of their companies, which are still run overwhelmingly by Americans or Europeans.

This is yet another example of action trailing ambition.

To accelerate growth in China, the country must be factored into all high-level decisions. To ensure this happens, China needs to be sufficiently represented on your leadership team, board of directors and other important decision-making committees. Again, positive discrimination may be required.

One way to keep China constantly on the mind of senior leadership is to fill top positions with people who know China.

Another way to factor China into high-level decisions is to restructure the top leadership team, which at most multinationals remains dominated by people based in the West.

One option is to promote the leader of China operations to that top team.

For example, Sam Su, head of Yum Brands (owners of KFC) in China, is one of the only geographic leaders among Yum Brands' senior officers, emphasizing how important China is to the company's future growth.

4. Are our corporate functions and capabilities in China as strong as they are at home?

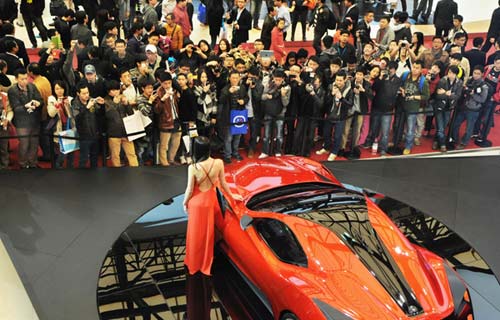

China is transitioning from the world's factory to its shopping center.

Designing growth strategies, developing a deeper understanding of customers, building brands, and attracting and retaining talented employees are now vitally important to success in China.

Yet few companies place the same emphasis on corporate functions and capabilities in China as they do in their home markets. R&D is a good example.

China today hosts about 1,000 foreign-owned R&D labs. However, these labs often focus on local adaptations of innovations rather than on developing cutting-edge technologies and products for global markets.

There have been some headline-grabbing examples of "reverse innovation," such as General Electric's ultrasound machine, a product developed in China and exported back to developed markets. But such examples are rare.

Most high-value R&D remains rooted in companies' home markets or other developed markets.

5. Are we taking a coordinated approach to China?

In an effort to quickly scale their businesses across borders, many companies have reduced the importance of their country managers in favor of product-led business units that span geographies.

Related Stories

Multinational corporation convention on Thursday 2012-06-28 13:16

Multinational firms becoming better corporate citizens 2012-03-14 13:24

Next wave of multinationals 2012-03-14 11:02

Multinationals keen to recruit Chinese execs 2012-02-01 08:58

Foreign CEOs believe good times can last 2011-12-09 08:10

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|