Where the iPhone work went

Updated: 2012-01-29 09:38

By Charles Duhigg and Keith Bradsher (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Getting the jobs

A few years after Apple began building the Macintosh in 1983, Mr. Jobs bragged that it was "a machine that is made in America." But, by 2004, Apple had largely turned to foreign manufacturing.

Asia was attractive because the semiskilled workers there were cheaper. But that wasn't driving Apple. For technology companies, the cost of labor is minimal compared with the expense of buying parts and managing supply chains that bring together components and services from hundreds of companies.

The focus on Asia "came down to two things," said one former high-ranking Apple executive. Factories in Asia "can scale up and down faster" and "Asian supply chains have surpassed what's in the US."

The impact of such advantages became obvious as soon as Mr. Jobs, dissatisfied with how easily scratched the iPhone's plastic screens were, demanded glass screens in 2007. For years, cellphone makers had avoided using glass because it required precision in cutting and grinding that was extremely difficult to achieve. Apple had already selected an American company, Corning Inc, to manufacture strengthened glass. But figuring out how to cut those panes into millions of iPhone screens required finding an empty cutting plant, hundreds of pieces of glass to use in experiments and an army of midlevel engineers. Then a bid for the work arrived from a Chinese factory.

When an Apple team visited, the Chinese plant's owners were already constructing a new wing. "This is in case you give us the contract," the manager said, according to a former Apple executive. The Chinese government had agreed to underwrite costs for numerous industries, and those subsidies had trickled down to the glass-cutting factory. It had a warehouse filled with glass samples available to Apple, free of charge. The owners made engineers available at almost no cost. They had built on-site dormitories so employees would be available 24 hours a day.

The Chinese plant got the job.

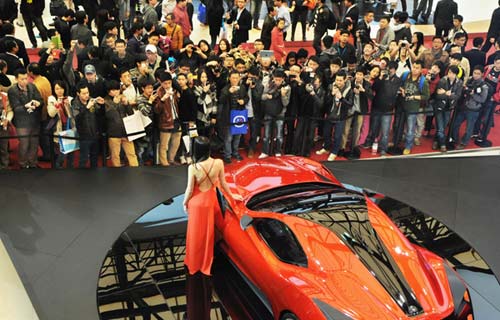

Chinese advantages

An eight-hour drive from that glass factory is a complex, known informally as Foxconn City, where the iPhone is assembled. The facility has 230,000 employees, many working six days a week, often spending up to 12 hours a day at the plant. Over a quarter of Foxconn's work force lives in company barracks and many workers earn less than $17 a day.

In mid-2007, after Apple's engineers perfected a method for cutting strengthened glass so it could be used in the iPhone's screen, the first truckloads arrived at Foxconn City in the dead of night, according to the former Apple executive. That's when managers woke thousands of workers, who lined up to assemble, by hand, the phones.

Foxconn Technology, in statements, disputed the former executive's account, and wrote that a midnight shift was impossible "because we have strict regulations regarding the working hours of our employees." The company said that all shifts began at either 7 a.m. or 7 p.m., and that employees receive at least 12 hours' notice of any schedule changes. Foxconn employees, in interviews, have challenged those assertions. Foxconn has dozens of facilities in Asia and Eastern Europe, and in Mexico and Brazil. It assembles an estimated 40 percent of the world's consumer electronics for customers like Amazon, Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Motorola, Nintendo, Nokia, Samsung and Sony.

Apple also said that China provided engineers at a scale the United States could not match. Apple's executives had estimated that it needed about 8,700 industrial engineers for the iPhone project. The company's analysts had forecast it would take as long as nine months to find that many engineers in the United States. In China, it took 15 days.

It is hard to estimate how much more it would cost to build iPhones in the United States. However, various analysts estimate paying American wages would add up to $65 to each iPhone's expense. Since Apple's profits are often hundreds of dollars per phone, building domestically would still yield a big profit.

But such calculations are meaningless because building the iPhone in the United States would demand much more than hiring Americans - it would require transforming the national and global economies. Apple executives believe America simply does not have the necessary factories or workers.

Related Stories

Apple pays user compensation over iPhone tracking 2011-07-14 16:16

Buzz abounds over iPhone 5 release 2011-09-16 10:39

iPhone app concerns family campaigners 2011-04-18 11:04

Apple talks to Hollywood about movie streaming: reports 2011-10-14 09:26

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|