Philippine discoveries show influence of Quanzhou

Bobby Orillaneda, a senior researcher at the Philippine National Museum of Anthropology, fell in love with ancient Chinese ceramics in 1999 when he joined a shipwreck excavation in Palawan, an archipelagic province in the Southeast Asian country.

As a ceramic researcher and head of the museum's maritime and underwater heritage division, Orillaneda says Chinese ceramics at the museum date to nearly 1,000 years ago, or the Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties.

The ancient Chinese ceramics, most of which were found at either inland or shipwreck sites in the Philippines, are "very good evidence of the thriving maritime trade between China and the rest of the world, including the Philippines", he says.

"Most of the collections here are from the port of Quanzhou in China's Fujian province, and date to the 13th century, when there was increased maritime traffic among China, the Philippines, and the rest of the Southeast Asian region. Ceramics from different areas of China would be carried to Quanzhou first and then shipped to different destinations such as here in the Philippines," Orillaneda says.

Over the years, Orillaneda has visited many cities in China to arrange cultural artifacts exhibitions. Among those cities, Quanzhou, the crucial starting point of the ancient maritime Silk Road, impressed him the most.

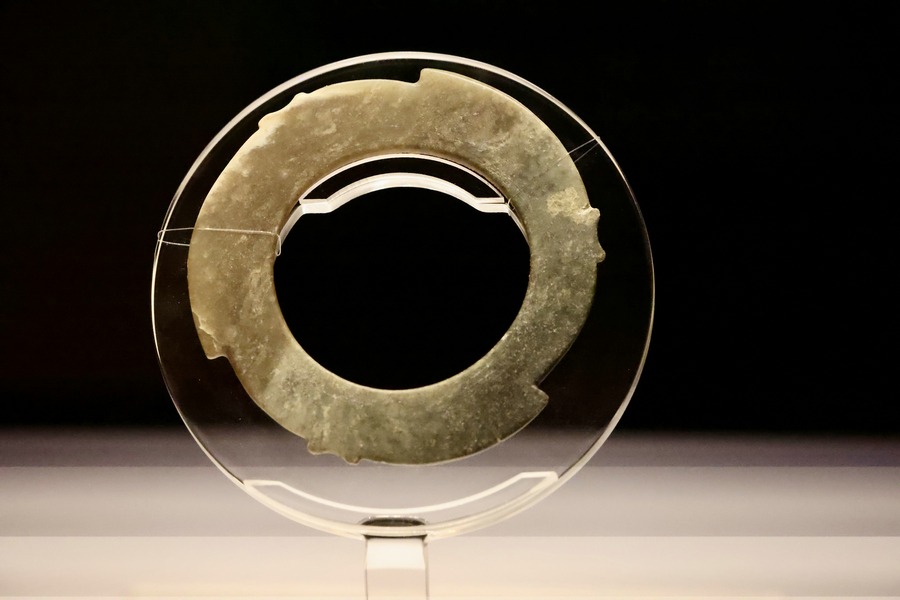

Dating to China's Song Dynasty (960-1279) and Yuan Dynasty, Quanzhou witnessed a prospering maritime trade and economy, serving as a bridge for cultural exchange and mutual learning between China and the rest of the world.

On Sunday, "Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China", was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List as a cultural site, bringing the total number of UNESCO World Heritage sites in the country to 56.

Starting from Quanzhou, silk, porcelain and tea were exported from China, while spices, exotic plants and other rare treasures were shipped back.

Shipwrecks excavated in Quanzhou Bay and the South China Sea also testify to the prosperity and vibrancy of the port, such as the wreck of a wooden-hulled sailing ship recovered from Houzhu Harbor in Quanzhou Bay.

This three-masted oceangoing commercial vessel seems to have been originally built in Quanzhou in the 13th century, and at the time of the wreck, it was returning from Southeast Asia loaded with spices, medicines and other merchandise.

Deeply engrossed in the study of ancient Chinese ceramics, Orillaneda says out of all the collections at the Philippine National Museum of Anthropology, his favorite one is a blue-and-white porcelain bowl made during the Yuan Dynasty.

"It was recovered from a late 15th century shipwreck here in Palawan, but this one is quite different because it is made during the Yuan Dynasty, which is about 100 years earlier than the shipwreck," Orillaneda says.

"During the Yuan Dynasty, the blue-and-whites were of a very high quality. The cobalt was taken from Central Asia and imported to China and used during the first batch of the blue-and-whites. Therefore, the exquisite craftsmanship and the colors are very vibrant. The design inside the bowl shows mythical animals like the phoenix and kylin, which are important symbols in Chinese mythology."

Orillaneda's mentor, Rita Tan, the former president of the Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines, has dedicated her life to studying ancient Chinese ceramics.

Born in 1939, Tan has been the curator of a series of exhibitions on overseas ancient Chinese ceramics, particularly those produced in Fujian province before being shipped from Quanzhou and finally discovered in the Philippines.

She attributes the discovery of Song-Yuan ceramics in the Philippines to Chinese government policy incentives of those dynasties and the Philippines' strategic location along the maritime Silk Road due to its proximity to China's coastal areas.

"The Song Dynasty was the 'golden era' of Chinese ceramics, which witnessed a boom in the construction of kilns in Southeast China. Moreover, the open policies and emphasis on foreign trade of those dynasties boosted the export of Chinese ceramics," Tan says.

"Geographically close, any ship traveling between China and the rest of the Southeast Asian region, and even Western Asia, would have to pass through the Philippines," Tan adds.