A tribute to a legendary diplomat

Digital copies of important documents kept by V.K. Wellington Koo have been given greater public access to commemorate his contributions to China and the world

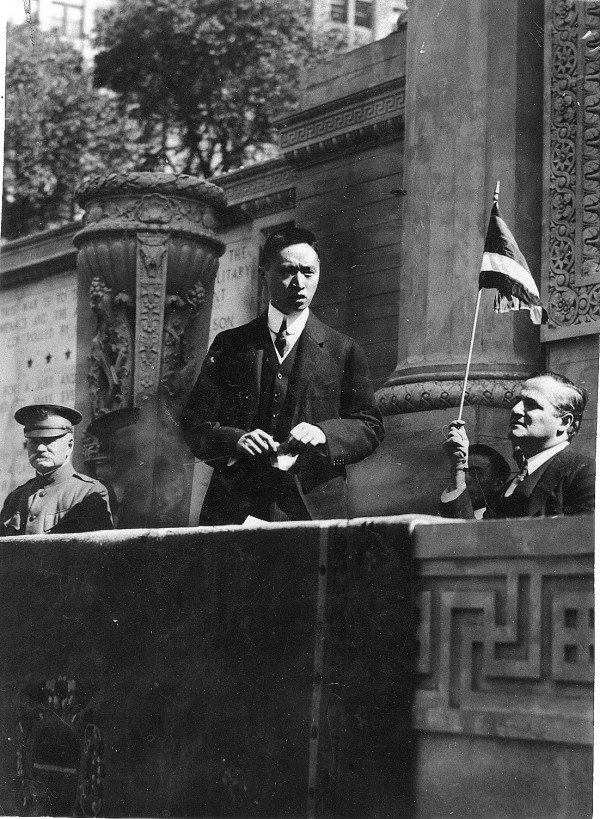

Almost a century ago, V.K. Wellington Koo made a decision that would steer the history of China and leave his mark on world history: he refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Koo was China's plenipotentiary to the Paris Peace Conference and his refusal was intended to be a protest to the conference as it had awarded Shandong province, which was formerly occupied by Germany, to Japan instead returning it to China.

During the conference, Koo collected correspondences, minutes and memoranda, and preserved these materials which later helped people to understand that moment in history.

On Dec 6, the digital copy of these documents, along with other materials from Koo's career which spanned from his days as a young diplomat to his retirement as a judge at the International Court of Justice at The Hague, were made accessible to researchers at Fudan University in Shanghai. The move to make public these documents is the latest effort of a joint project by Koo's children, Columbia University and the Institute of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences to make this man's legacy more known to the public.

When studying the history of China's modern diplomacy, one cannot ignore Koo, or Gu Weijun in pinyin. He served as Chinese ambassador for three major powers — the US, France and Britain — and held various important government posts, including foreign minister and interim prime minister. He was also involved in the founding of the League of Nations and the United Nations as China's delegate, and had witnessed the Kuomintang's loss of power in international organizations to the Communist Party of China.

And just like the case at the Paris Peace Conference, he kept records to all these important moments.

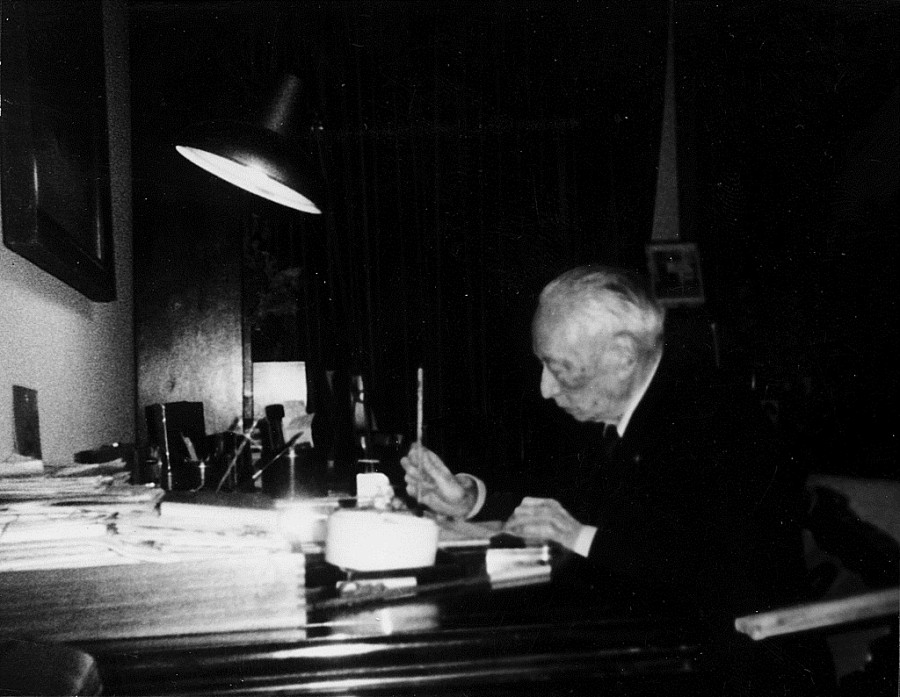

When Koo retired in 1967, he moved to New York and participated in an oral history project by his alma mater, Columbia University, in which he said: "Since the early years of my career, I have always been keenly interested in preserving for future generations important diplomatic communications and references."

Koo also donated 225 boxes of documents to the university. These documents include files of telegrams regarding domestic and international affairs, notes taken during his conversations with world leaders, and his correspondence with notable figures such as Chiang Kai-shek, Soong Mei-ling, and Thomas E. Dewey.

Sean Quimby, director of Columbia University's Rare Books and Manuscript Library, said in an earlier interview with China Daily: "The Koo archive consists of meticulously written notes of conversations with various figures, including at least three presidents of the United States."

After Koo died in 1985 in New York, his family again donated 57 boxes of his documents to the university archive.

Shirley Young, the step daughter of Koo, said: "I once learned from the Columbia University that there were only a few people using Koo's archive. The university has done its job in preserving it, but I hope the papers will be better utilized."

Jin Guangyao, a history professor at Fudan University, was one of those who made use of this archive. He went to Columbia University in 1997 and spent a year going through these papers in order to write a biography of Koo.

"Back then, I had to transcribe the parts I needed," he recalled. "I'm sure a digital archive will benefit many researchers in China."

Later, Jin helped Young establish contact with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The Institute of Modern History at CASS had in 1983 translated and published Koo's oral history, and was very interested in the papers. From there, the joint project of digitizing Koo's papers started.

Since 2014, Columbia University has scanned around 180,000 pages, while the researchers of the institute were tasked with cataloging. The result is a 26-gigabyte database comprising 74,000 entries.

The digitized papers were then copied by the institute and made accessible in Beijing in January.

Ma Zhongwen, director of the archive department of the institute, said that while the database is not open to the general public, it is nonetheless easier for researchers to access it.

Many scholars from universities around China have come to the department to read the papers. "In the past, the most-used archive in our department is Hu Shih's, but this year it's Koo's," Ma said.

Koo's family members have also agreed to give a copy of the database to Fudan, given the university's expertise in historical studies and the fact that Koo was born in Shanghai.

According to Fudan, the database will be open to graduate students, professors and visiting scholars.

A museum dedicated to Koo in Shanghai's Jiading district, where he was born in 1888, was also renovated and reopened on Dec 8 with new items donated by family members. The ceremony was followed by a concert at Jiading Poly Theater that depicted Koo's life.

"It's like my father's legacy is finally coming back to home," Young said.

Zhang Kun in Shanghai contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at xingyi@chinadaily.com.cn

- Doctor injects child with improperly stored drug at Chongqing hospital

- Xi's special envoy attends forum dedicated to Intl Year of Peace and Trust in Turkmenistan

- Memorial ceremony remembers victims of Nanjing Massacre

- Louvre's largest showcase in China goes on display at Museum of Art Pudong in Shanghai

- Indonesian foundation to fund students, school administrators to exchange and study in Tianjin

- Archives detailing crimes of Japanese unit released