Coordinating a market economy

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

Coordinating a market economy

Editor’s note:Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation’s journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Keep track of the story by following us.

The author, left, presenting his book China's Century to Premier Zhu Rongji. [Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn]

I first met Zhu Rongji in 1988 when he was the charismatic mayor of Shanghai. Before Zhu became mayor, investing in Shanghai was a challenge for foreign investors. Shanghai’s bureaucracy was convoluted. Because so many different approvals were needed for everything and each department refused to cooperate with the others, nothing ever got done.

As mayor, Zhu’s first challenge was to bring in foreign investment. He called all of the departments together, put them in a single room and created a one-stop shop for investors. He called it the “investment dragon line”.

I was invited to Shanghai as part of a Hong Kong-American Chamber of Commerce delegation to understand how the “dragon” worked.

Zhu received us in an old 1930s-style hotel, amidst dark red satin curtains and art deco chairs. He arrived a bit late and in a rush. Wasting no time, he talked about his one-stop shop to make investments smoother for everyone. One Hong Kong business leader sitting next to me noticed Zhu was wearing hiking boots under his suit trousers. The businessman whispered snobbishly how in China even the mayor of an important city like Shanghai could not dress properly. Before ending the meeting Zhu apologized for arriving late, explaining he had just come from a construction site, which was why he was wearing hiking boots. As mayor, he was personally overseeing every investment project to assure it proceeded without delay.

I left the meeting impressed and a bit stunned by Shanghai’s new mayor. At that moment, nobody could imagine Zhu would become a driving force in China’s transition during the 1990s and the emergence of a macroeconomic control system that would become known as economic sequencing. That simple “investment dragon line”, bringing uncooperative government departments together in one room where they would have to coordinate and cooperate, was a prototype that would change China’s purely centrally planned economic system.

Change began in February 1991 during Chinese New Year, when leaders visiting Shanghai realized socialism as it was being practiced — within the framework of an entirely planned economy inherited from Soviet advisors in the 1950s — could not support the need for progressive reform and opening-up. While the old planned system had solved immediate problems and social discrepancies post-World War II, in the long term it discouraged growth and entrepreneurial spirit. Zhu was then promoted from Shanghai mayor to the position of Vice-Premier of the State Council in charge of industrial production. But production was not the issue; rather, coordination between different industrial departments functioned on the basis of state plans, leading to inefficiencies.

Shortly after assuming his position as vice-premier, Zhu established an organization called the Production Office of the State Council, which he personally supervised. When Zhu became State Council Premier in 1998, the office became the State Economy and Trade Commission, with overarching powers to coordinate industrial investments and trade, and untangle the often contradictory mish-mash of ministerial powers.

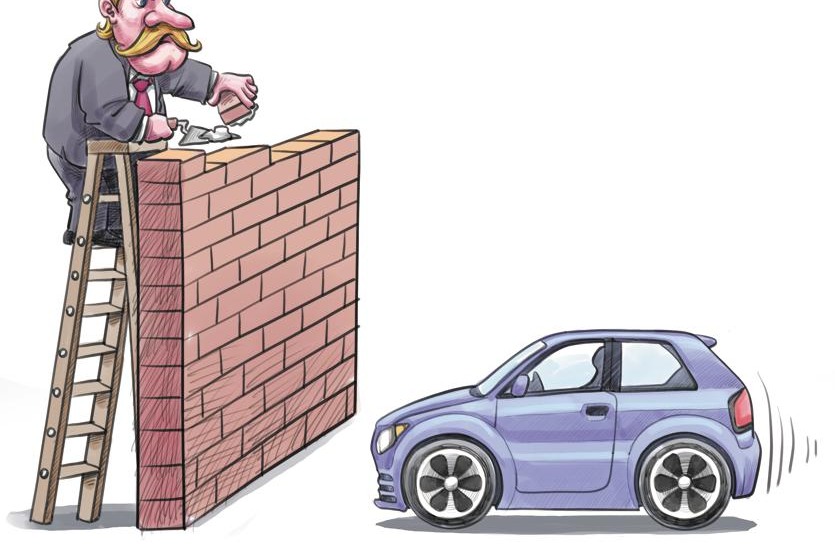

Soviet planning left China with a separate ministry for each industry. There were also functional ministries like transport, commerce and healthcare. All functioned in a command system, top-down within their own ministry, but also refused to take a command from any other ministry. So none of the ministries worked together, and there was no horizontal communication. Policy could not be coordinated.

Take the simple manufacturing of a car. The State Planning Commission set the plans. The Ministry of Finance paid for them. The Ministry of Electrical Engineering oversaw car industry production. There was also the Ministry of Steel and Ministry of Chemicals, who provided the parts. The Ministry of Transport oversaw transport of cars once they were made, and all the licensing to get them on the road. They wanted their cut, too. The Ministry of Railways set their own quotas for how many cars could be transported by rail, regardless of the market — they could not care less, which meant they interfered with the Ministry of Transport’s job. The Ministry of Commerce determined how cars could be sold and where. But how many? For the answer, they had to go back to the Ministry of Planning. A pricing department there set the amount. It went on like that in endless convolution. Nothing could get done.

Zhu was basically creating a “mega-ministry” to communicate with the bodies that refused to speak to each other. He was essentially taking that one-stop investment shop model from Shanghai to a national level. His new organization, which started as the Industrial Production Office of the State Council, soon imploded. For five years the newly transformed State Economy and Trade Commission would coordinate all production, commercial, transport and market policy. It would untangle the imbroglio by breaking down barriers between line ministries and downsizing them. These industrial ministries would eventually be wiped out altogether, their remnants becoming mere chambers of commerce — such as the Textile Manufacturers Chamber or the Light Industrial Manufacturing Chamber.

Within just a few years the seemingly stagnant legacy of Soviet command economics was transformed into a coordinated market economy, rebalanced through guidance and a healthy dose of good old-fashioned long-term planning.

Please click here to read previous articles.