flash

In the eye of the storm

Updated: 2011-07-10 08:49

By Han Bingbin (China Daily)

|

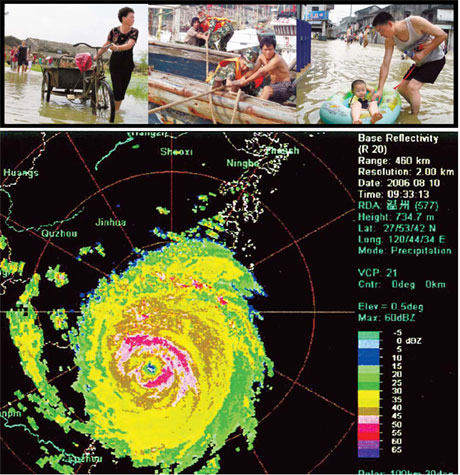

Top from left to right: When Typhoon Saomai struck in 2006, residents were caught unprepared and the storm caused a lot of damage, leaving physical and psychological scars. Below: An image of Typhoon Saomai on the radar map shows the eye of the storm centered over the Zhejiang coastal regions. [Photo/Agencies] |

Every year, they risk their lives and their homes when the "big wind" strikes. Yet, those living in the paths of the seasonal typhoons have a reason for staying where they are. Han Bingbin goes storm-chasing to find out the reasons why.

When the faint breeze of a summer night fills the air with the strong smell of fish and sea mud, the fishing town comes alive. Under the dim halo of streetlamps, men drink and shout greetings to each other at the roadside food stalls. Across the street, the women giggle as they indulge in gossip, interrupted now and then by a baby's insistent wail.

In the neighborhood, the sound of mahjong tiles clacking against tables rises in waves as the games progress. And in the background, the waves lap at the shore, gentle as a snoring puppy, as the sea slumbers by the seaside town.

The town is Xiaguan, located at the southern end of Cangnan County in Zhejiang province. Here, more than half the 22,000 residents make a living fishing for the tiny shrimps they call xiapi, a sort of krill, which is then sun-dried and packaged.

The fishing season lasts from October to January, and there is a ban for the rest of the year to allow the tiny crustaceans to revive their numbers. A sustainable fishing cycle means a pleasant pace for the fisherfolk, who work hard for four months each year and then can afford to relax from June to September.

During this time, members of the fishing fleet have little to do, apart from attending government-sponsored training courses, and maintaining and repairing their boats and equipment. It is also time to relax a little, as they reward themselves with some of life's little pleasures.

But this off-peak period also brings a seasonal threat that shatters the illusion of an idyllic life.

Xiaguan is right in the path of the summer typhoons, and an average of three will wreak annual havoc on life and property each year.

Though the storms would blow down a few ramshackle huts and kill the occasional fisherman foolhardy enough to risk going to sea in spite of storm warnings, Xiaguan residents hardly saw the typhoons as a deadly threat before.

In 1958, the strongest typhoon within memory destroyed much property and since then, in the words of 55-year-old Liu Jijie, subsequent typhoons have "rarely been a big deal".

In the aftermath of the storm, huge waves battered the harbor front.

For 19-year-old Jiang Zuquan, the worst thing a typhoon did was to take off the door of his house. For most of the townfolks, typhoons were just inconvenient storms with heavy rainfall that caused floods and landslides. You stayed indoors during the typhoons. At least, the women and children did. Some of the men would proudly boast about how they stayed on their boats in the harbor - boats that they cherish more than their lives.

|

In the aftermath of the storm, huge waves battered the harbor front. [Photo/China Daily]

|

That was how it was, until 2006 when Typhoon Saomai struck - the strongest storm to hit the country in 50 years. In China, it killed more than 480 people and left more missing. It also destroyed more than 50,000 homes.

In Xiaguan, it left 28 dead, some killed when their houses collapsed while others were just swallowed up by the waves. In the town, more than 1,000 homes were destroyed. The scale of destruction made sure this was a storm people would remember.

August 10, 2006 was a bright sunny day, although the residents had been warned that an exceptionally strong typhoon was heading that way. The people did not take the warnings too seriously and the men stayed on their boats, assuming they would be well-protected within the harbor.

Because of the low tide, several thousand ships were aground. At about 4 pm, a strong gust from the northwest tilted several ships.

That still didn't scare fisherman Qiu Jianshi, who hurriedly tied down his ship when there was a pause between the gusts. Before he had time to clean up and return to shore, however, a much heavier gust raised a mountainous wave that rushed straight at the harbor.

"It looked like the tidal bores of Qiantang," he remembers. His 20-meter long vessel was upended and capsized and he also went under water. Minutes later, as he struggled to surface, he found a larger ship beside him and clambered aboard - a move which saved his life. When he recovered enough to look around, he saw nothing. All the boats, including his, were gone.

"It was total chaos," he recalls. Hours later when the wind finally stopped, he found out that hundreds of ships in the harbor had been swept away.

The next morning, Qiu woke up to a scene he would never forget. Tiles from roofs littered the roads. Dead bodies were flung up on the beaches after the tide ebbed. People were crying bitterly all about the town.

Even now, the mention of Saomai is enough to turn faces pale, as the locals remember the physical damage and mental trauma. Saomai brought home the message that life in the paths of the typhoons is fragile.

Xiaguan started experiencing changes. First, the architecture of new houses reflected the insecurity and fear. From the simple wooden structures of before, new houses are now made from ferroconcrete and constructed to withstand very heavy storms.

Cai Zusheng, who had his brick-and-stone home blown away during Saomai, spent as much as 100,000 yuan on his new house. He is proud of its reinforced structure.

"I used a lot more concrete. All is top quality," he says. The first requirement is a solid foundation. Ferroconcrete, as opposed to normal concrete, has iron compounds bonded into the concrete and is a reinforced building material. Foundations used to have only two structural beams; they now have five.

A more profound and fundamental change is the attitude towards the typhoons. There is now a tangible fear that brings out a sense of crisis.

Previously, community leaders had to go knocking on doors to warn those living near the sea to move to safer grounds. Now, Shi Zhengzhong, 36, is typical of how residents are a lot more aware of impending storms. He spends a lot of time scanning weather forecast websites when a typhoon approaches, ready to move inland if there is a threat.

Many think even further ahead and some homes are stocked up on drinking water, instant noodles and flashlights in case they get stranded during a typhoon.

Owners of boats and ships are also more concerned about safety, as marine police officer Liu Weihua discovered. When he went on an annual safety check of the vessels, he was surprised to find all ships now equipped with life jackets. Before 2006, he had to throw the weight of the law at owners before they would comply with the regulations.

Liu also observed a new trend. Before 2006, some ships would go to sea alone. These days, they tend to sail in small fleets of three to five, so they could help each other in case of danger.

The fishermen sense that the typhoons are getting stronger and more ferocious each year. Qiu Jianshi says perhaps this is because of the changing climate and global warming, but he fears a second Saomai.

But asked if he would move, Qiu frowns and says the thought has never occurred to him.

"It makes no difference if we just move to another part of the county. There will still be typhoons," he says, mulling the question.

"We rely on the sea to make a living. It's hard to move to a totally new environment and start a new life. Most of the folks here are not well educated. Many of my father's generation are even illiterate."

Town official Xu Yunshui says fishing is still an attractive livelihood that brings in a decent income - which explains why most are reluctant to move.

Xu says the dried baby shrimps sell well all around China, and they are exported to South Korea. In a good year, a fishing boat can bring in about 300,000 yuan. As each vessel may be shared by three families, it means each household can expect an annual income of 100,000 yuan at best. By rural standards, this is not something to sneer at.

The fact that the typhoons come during the off-season for the fishing fleets is a blessed coincidence, so they do not directly affect the business.

The truth is, the people of Xiaguan are ambiguous about the typhoons. While the storms herald fear and trouble, they also help the town.

Heavy rains add to the town's reserves of fresh water.

More significantly, the huge waves brought by the typhoons also stir up plankton and bring it to the surface - food for the precious shrimps that will grow fat and abundant later.

That is why, Xu says, that in the years with the strongest typhoons, there is usually a good harvest.

Contact the writer at hanbingbin@chinadaily.com.cn.

E-paper

Burning desire

Tradition overrides public safety as fireworks make an explosive comeback

Melody of life

Demystifying Tibet

Bubble worries

Specials

90th anniversary of the CPC

The Party has been leading the country and people to prosperity.

Say hello to hi panda

An unusual panda is the rising star in Europe's fashion circles

My China story

Foreign readers are invited to share your China stories.